Finding these hydrocarbons is as difficult and complex as you might imagine. Yet developing these hydrocarbons—getting them out of the earth, essentially—might be an even greater challenge. Not because of the engineering, but rather the business diplomacy required. If the companies and countries involved in a project can’t agree on the economics and particulars, then the hydrocarbons remain untapped.

Diplomacy, in other words, often acts as the crucial bridge between the discovery of hydrocarbons and their valuable development—and in 2015, Kosmos Energy had to build that bridge between Mauritania and Senegal, two countries that had fought a border war less than 30 years before.

In 2011 Kosmos’ geologists and geophysicists looked at the results of more than 50 unsuccessful wells that had been drilled offshore Mauritania. Previous exploration efforts focused on shallow water relatively close to the coastline and in onshore areas, but Kosmos hypothesized the wells had been drilled in the wrong place: Pre-historic river systems had pushed hydrocarbon-rich reservoir sands further offshore.

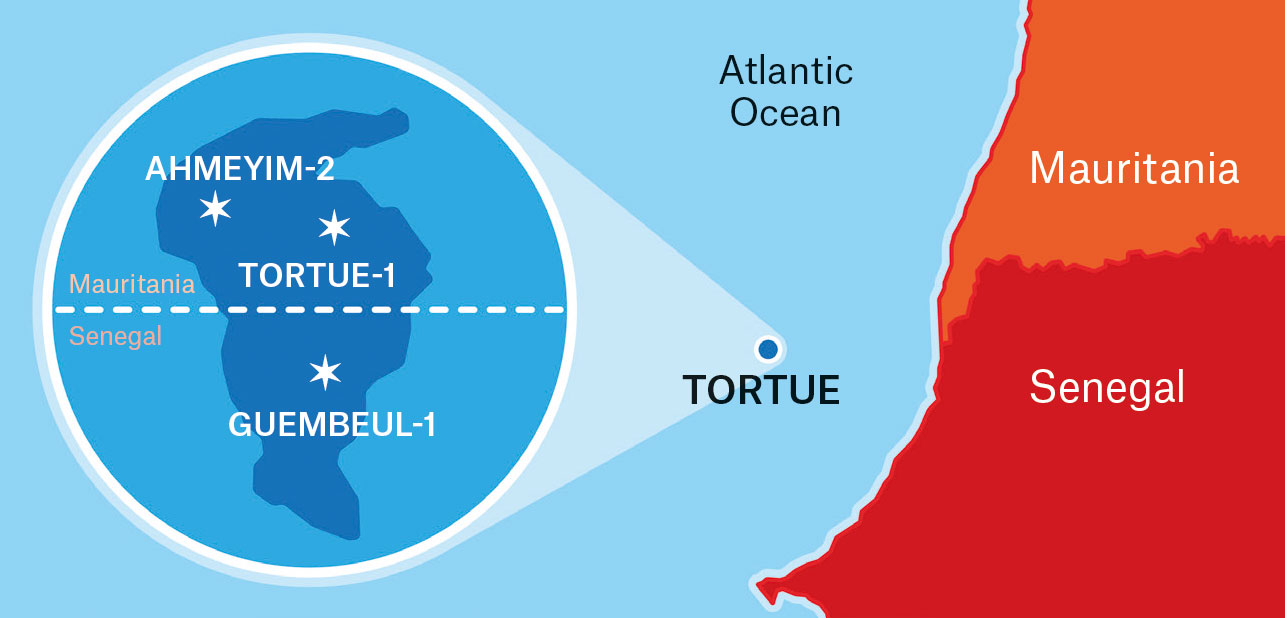

Kosmos acquired several blocks offshore Mauritania, where 2D and 3D seismic surveys later showed a large, promising geological structure—the kind capable of supporting hydrocarbon reservoirs. This structure appeared to extend across the maritime boundary from Mauritania into Senegal, where Kosmos acquired further exploration blocks. Drilling its first exploration well offshore Mauritania in early 2015, Kosmos found the largest natural gas field offshore West Africa in history.

Over the following 18 months, it drilled five additional exploration and appraisal wells, including two in Senegal. All were successful.

The largest known deposit, Greater Tortue Ahmeyim, “contains at least 15 trillion cubic feet of gas, enough to generate billions of dollars of export revenue and is of a scale that would meet the UK’s total natural gas demand for roughly five years,” says Kosmos Energy Chairman and CEO Andrew Inglis. In addition to its size, there was another remarkable feature about Tortue: It was split with almost geometric precision between the maritime boundaries of the two countries.