When a crisis strikes, do you hit back with an aggressive plan to engage your critics and explain what you are doing better? Or do you hunker down and wait for the storm to pass?

By Brunswick’s Robert Moran and CoreBrand’s James R. Gregory

Would you change your answer if you learned that it would take nearly four years for your company to restore its pre-crisis reputation – nearly as long as the average tenure of today’s CEO?

The approach to communicating through a crisis is critically important. But there hasn’t been much data to show how these diametrically opposed strategies serve the corporate leaders who chose them. And in the midst of a crisis when emotions are running high, objective analysis is even harder to come by.

Brunswick partnered with brand analytics and tracking firm CoreBrand to analyze how quickly and effectively companies were able to emerge from a crisis. The findings should be sobering for all corporate leaders – primarily because it took so long to recover, no matter what strategy was adopted.

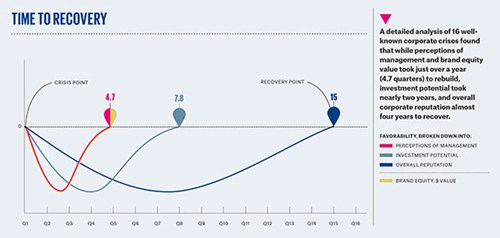

Looking at 16 well-known crises at Fortune 500 companies, we found that the average time to restore corporate reputation was nearly four years. Digging into CoreBrand’s extensive, 24-year database of business decisionmaker perceptions of more than 1,000 companies across 54 industries, we found that the average time to rebuild perceptions of investment potential was nearly two years, an eternity in the stock market. And the average time for return to pre-crisis brand equity value was just over a year, not good news for the Chief Marketing Officer.

This presents three significant implications for management:

- Managing expectations: Prepare the board for a long, hard slog back to pre-crisis levels of trust among customers, employees, investors and other stakeholders.

- Rebuilding: Once news coverage of the crisis has subsided, management needs to pivot from firefighter mindset to a rebuilding mentality. A plan to restore reputation is needed in order to reduce the duration of the post-crisis slide.

- Employee morale and attrition: Many high performers decide to jump ship in the aftermath of a crisis. Our findings suggest that unless they want to wait out a two- to four-year slide, their decision is entirely logical. Companies need to focus on values, morale and compensation as tools to retain high performers in a post-crisis environment.

Does becoming more “familiar” mean you fall out of “favor?”

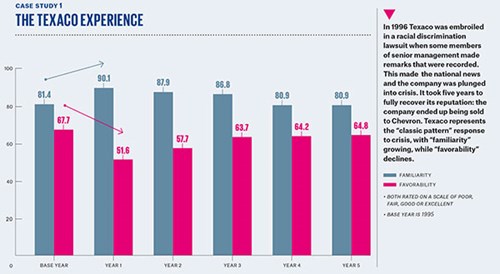

From a perception standpoint, when a crisis hits, we see an increase in “familiarity,” as measured in CoreBrand’s survey of business decision makers by the level of awareness in the marketplace. This may be affected by a media feeding frenzy over a negative story, for example.

Our data finds that a proactive response to a crisis can further increase familiarity, beyond the initial crisis level. And increasing familiarity can be accompanied by lower “favorability,” measured by quality of reputation across three key attributes: overall reputation, perception of management and investment potential.

This analysis leads us to a definition of crisis: when familiarity increases and favorability declines dramatically.

Our research shows two distinct approaches to how companies lead through crisis. Some choose a more demonstrative path (the “classic” pattern) while others choose to reduce their exposure (the “quiet” pattern).

These approaches represent two competing schools of thought among those who have to deal with crisis situations. One argues that it is best to be the bearer of your own bad news and that failure to engage the media and stakeholders in a transparent world will only cause long-term pain.

The other says that in an age of hyperactive distraction, in which consumers are drowning in messages that they constantly scan but seldom engage deeply with, it is best to deprive the crisis of additional oxygen and “let it blow over.”

Seven of the 16 companies in the study exhibited the classic pattern: the company is initially knocked back on its heels but soon begins engaging stakeholders to either explain its side of the story or to show how it is mending its ways.

But nine of the 16 had a response that surprised us: the quiet pattern. These companies exhibited similar declines in their reputations, but became less “familiar.” The crisis takes its toll, the company keeps a low profile, falls out of the headlines and begins to drop from the consciousness of business decision makers.

The correct course is not always obvious in the middle of a crisis, and choosing between these approaches presents a high-level strategic decision at a time when the public’s trust in institutions and business could not be lower. From the “Occupy” movement’s critiques to the recently coined term “bankster,” the current zeitgeist is anything but business-friendly.

Which crisis response behavior is more effective? Should a company fly low – or engage aggressively?

The low flyer (quiet pattern) companies actually suffered slightly fewer hits to their favorability and overall reputation. And perceptions of management took only half the hit that they took among the engaged ones (classic pattern).

At first blush – and ethical considerations aside – it appears that flying low is a stronger strategy.

But, there’s a catch. The low flyers appear to suffer a longer downturn in their brand equity. The brand strength of those hunkering down, as measured by CoreBrand, took longer to bounce back. Whereas the engaged group actually began to repair their brand after one year, the disengaged group were still stuck in negative territory with losses in brand equity as a percentage of market cap.

The “fly low” strategy has other potential drawbacks. There are greater threats of government intervention as stakeholders demand more accountability, and there are the quiet and negative impacts of corporate silence on internal morale.

Even in the age of transparency, disengagement may be a valid short-term survival strategy, but it appears to pose greater challenges to the health of the brand. Silence is not always golden.

And, given the average length of time that it takes to repair corporate reputation (almost four years), rebuild perceptions of investment potential (nearly two years) and return to pre-crisis brand equity value (more than a year), engagement and repair seem to be the wiser, long-term approach.

When the fire is over and the firefighters have extinguished the blaze, the builders need to begin their work.

FAMILIARITY: Defined by the level of awareness in the marketplace, as measured by CoreBrand’s survey of business decision makers.

FAVORABILITY: Measured by quality of reputation across three key attributes: overall reputation, perception of management and investment potential.

CRISIS DEFINED: When “familiarity” increases and “favorability” decreases dramatically.

This article is also available in Chinese. Click here to download the PDF.

Brunswick Insight

- ROBERT MORAN is a Partner in Brunswick’s Washington, DC office and leads Brunswick Insight in the Americas.

- BRUNSWICK INSIGHT is the strategic research function of the Brunswick Group. It uses opinion polling and qualitative research to analyze perceptions about companies and issues, pinpoint messages that resonate, and craft strategies to build support.

CoreBrand

- JAMES R. GREGORY is the founder and CEO of CoreBrand. He has written extensively on creating value with brands.

- COREBRAND helps organizations understand, define, express and leverage their brands for measurable results. Founded 40 years ago, it focuses on using quantitative research to help senior corporate leaders manage their corporate brands by understanding the impact of various events, including crises.