In 2018, Justin Timberlake announced he would perform alongside a Prince hologram at a Super Bowl performance, as a tribute to the musician who died suddenly in 2016 at the age of 57. The outcry over Mr. Timberlake’s announcement was immediate and widespread. Such an event, fans and people close to the late performer believed, would trivialize and exploit the artist’s legacy. Even worse, it ran afoul of The Artist himself. In an interview with Guitar Player Magazine in 1998, Prince was asked if he would ever jam with an interactive recording of a dead musician. “Certainly not,” he replied. “That’s the most demonic thing imaginable. Everything is as it is, and it should be. If I was meant to jam with Duke Ellington, we would have lived in the same age.”

A different set of ethical concerns surround the rise of anime character holograms. Akihiko Kondo isn’t alone in marrying one. Japanese company Gatebox makes a small glass-domed device that houses a tiny holographic anime girl. The company is marketing it as a wife stand-in to “single men who live alone” and has issued thousands of “marriage certificates.” It doesn’t take a psychology degree to suspect this could aggravate existing social dysfunctions.

Count the family of Mr. Kondo among the objectors. Not one of them attended the $18,000 wedding, in which Mr. Kondo used a stuffed doll as a stand-in for the hologram, which resides in his home via a desktop device. The law is not on his side either as the marriage is not legally binding.

Many of these social and cultural concerns may be simply a factor of the newness and strangeness of the technology itself. The earliest films amazed audiences with thrills the new medium made possible. At the end of the 1903 silent classic “The Great Train Robbery,” a grim outlaw points his gun directly into the camera lens and fires repeatedly—terrifying in 1903, the effect now seems positively quaint. Our reactions have evolved with the medium.

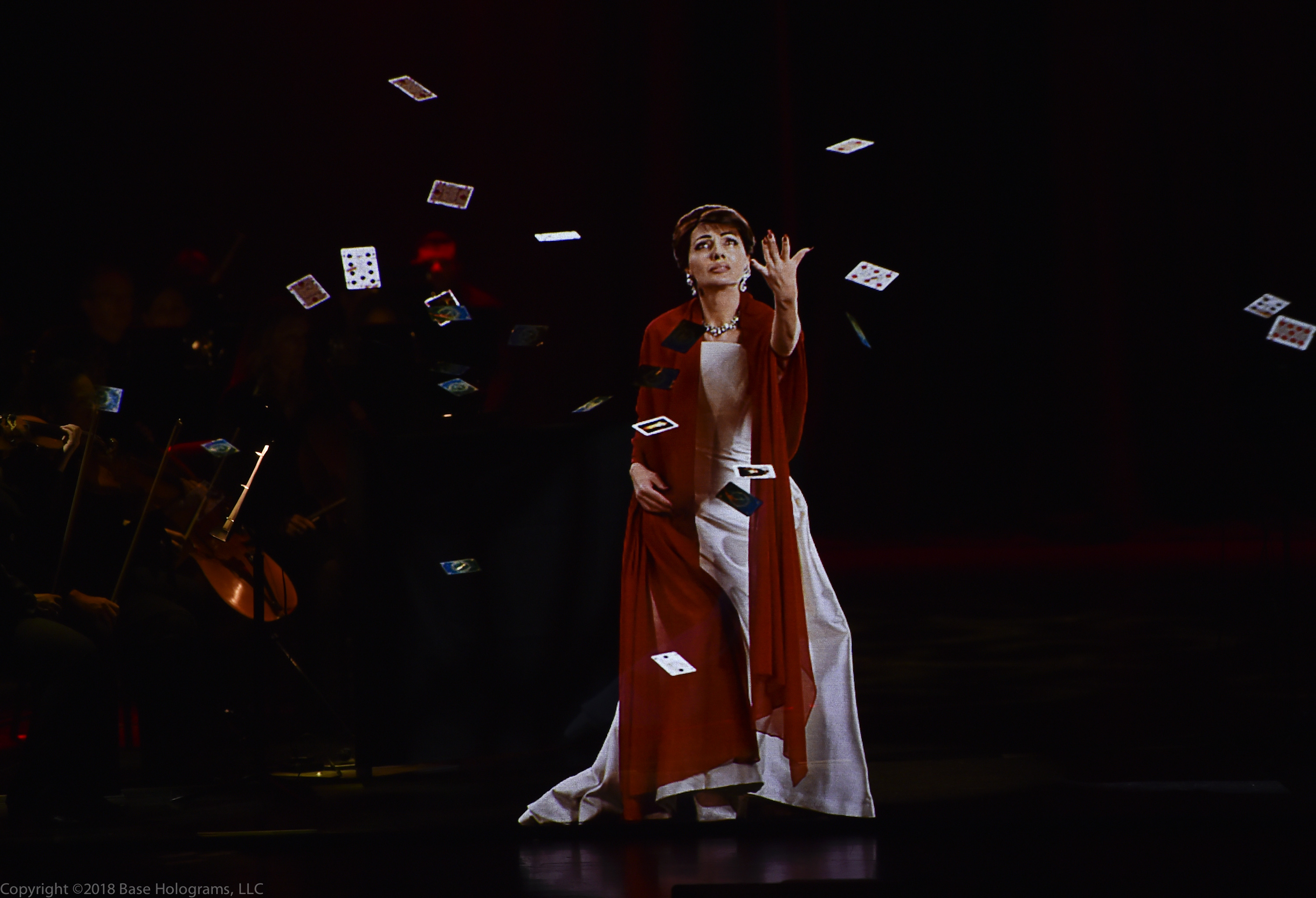

Mr. Becker sees this strangeness as one of the main concerns of BASE Hologram. He wants people to view holographic performances as an exciting entertainment choice—on par with a Broadway show or a movie—rather than as a novelty. “We have to stay diligent on communicating what we’re doing, what people will see when they get into the theater.”

Once the audience is in their seats, he says, the experience speaks for itself. Take the Roy Orbison show, for instance.

“The first song, people are tweeting, ‘Oh, I can’t believe how lifelike.’ The second song, they start to get into it. The third song, as they recognize the first few chords of an old hit, they start applauding—they’re showing their appreciation and encouragement to the artist, right? You would do that at a Springsteen concert, with a live performer. In this case, the artist is a holographic image. That means they have suspended disbelief and they’re allowing themselves to simply enjoy the show.”

PROJECTING THE FUTURE

For living artists, the use of holographic events may help to grow their reputations with new audiences, and to extend and secure their legacies in new ways. Abba, whose four original members are all still with us but haven’t performed as a unit since 1984, is one group that is seeing the opportunity. A tour of holographic concerts is being prepared, featuring the band members as their younger selves. It may even feature new songs, recorded especially for the tour by the reunited quartet.

In 2011, Mariah Carey made headlines with a holographic recording of Christmas songs that was presented as concerts in public squares in five European countries simultaneously. The singer was flanked by virtual dancers in gray suits and similarly attired live dancers.

The package was part of a promotional campaign created for Deutsche Telekom. And it points the way to the future: commercial applications guaranteed to make the technology more common in our daily lives.

“Think about all the artists that have done Christmas albums and how cool it would be to have some of them—Bing Crosby and Nat King Cole—singing Christmas songs at major malls around the country, around the world,” Mr. Becker says.

From there, it’s a short step to seeing these effects in all aspects of business and entertainment. Mr. O’Connell of Musion 3D sees a long list of opportunities ahead.

“This includes live speeches from CEOs at their corporate events or politicians using our technology to appear live as a hologram in remote locations,” he says. “Our technology is also used to launch products or increase brand recognition. It lends itself well to the car industry when a new model that is not freely available can be replicated as a lifelike hologram. Many theme parks now use holographic technology as part of their attractions.”

Similarly, Crypton Future Media, developers of the vocaloid Hatsune Miku, is “always on the lookout for new collaborations with businesses and professionals all over the world,” Mr. Itoh says.

Looking further ahead, Mr. Becker speculates about curved projection technology that will allow hologram-style illusions to include three dimensions, or of even more sophisticated interactivity that would allow participants to step into imaginary scenes, such as the famous “Star Wars” Cantina, populated by holographic aliens.

“The whole technology area that we’re taking advantage of is actually being robustly developed and improved by other industries—not by ours, necessarily,” he says. “Look at how it’s being used for teaching medical students. There’s a whole host of other uses for this technology. We’re just one of the beneficiaries.”

That perspective implies a dose of reality not just for this nascent entertainment sector but for all communications featuring cutting-edge technology: The focus needs to be not on technological innovation but on content, and how it can be reshaped by the newly available resources.

“I didn’t think to myself, ‘Hey, I want to be in the hologram business,’” Mr. Becker says. “What I thought was, ‘There’s a lot that we can do with this technology to put on a better show.’

“At the end of the day, it’s character, it’s story and it’s music. If we don’t deliver on that, it doesn’t matter what our technology is.”