Journalist and author Salena Zito explains how “shoe-leather journalism” allowed her to see what sophisticated polling had missed about Donald Trump

In September of 2016, as part of a downsizing at the daily Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, where she had worked more than a decade, Salena Zito took a buyout. Cast amid the swelling ranks of out-of-work journalists, Ms. Zito had one advantage: That July, she had written a column predicting that Donald Trump would win the upcoming US election.

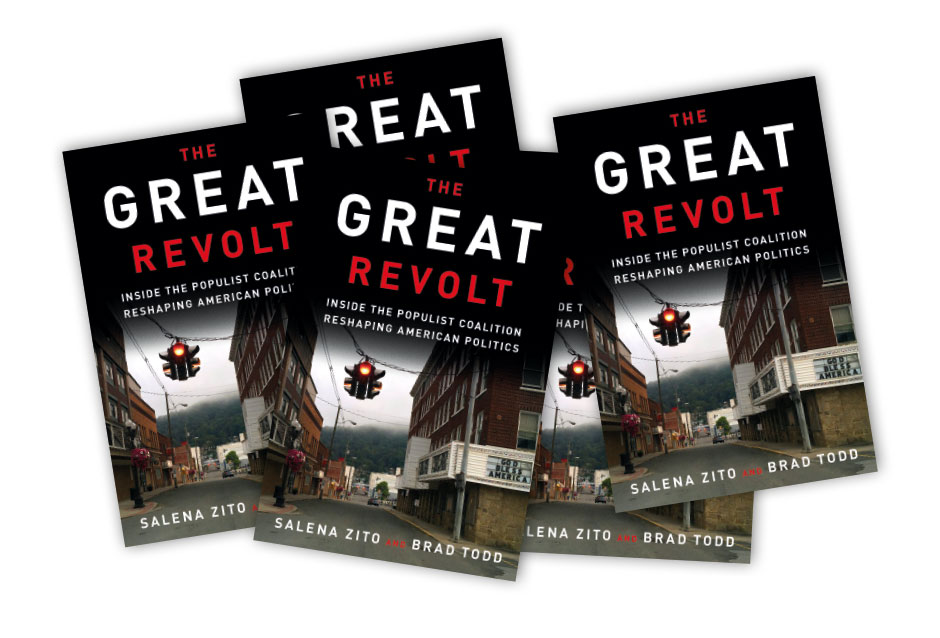

When that well-researched and highly counterintuitive forecast proved to be accurate, demand surged for Ms. Zito’s talents as a journalist. She now writes a weekly column for the New York Post, near-daily articles for the Washington Examiner and serves as a regular contributor to CNN. A book contract she received after the election resulted in the publication this spring of The Great Revolt: Inside the Populist Coalition Reshaping American Politics. Her coauthor was Republican strategist Brad Todd.

Ms. Zito’s recent success illustrates the career-making potential of a prescient prediction. It also shows the limits of journalistic analysis of voting data, and of observing America from Washington.

A lifelong resident of Pittsburgh, Ms. Zito covered the 2016 campaign from the living rooms of voters all across Pennsylvania, a crucial swing state. In an interview in July with Brunswick Partner Mike Krempasky, Ms. Zito explains how she foresaw what so many pundits missed in 2016, and looks ahead to the November mid-term elections.

On what basis were you able to call the 2016 election for Trump several months in advance?

In July of 2016, I drove through all 67 counties of Pennsylvania and found a couple of things that were surprising. One was the number of Trump signs. It wasn’t only the number of signs, but that they were homemade. That’s a different level of intensity. I saw houses painted with Trump on the side. I saw barns, I saw a horse with Trump painted on its side. Also, these signs were in areas that weren’t traditionally Republican, that had no business of showing this much enthusiasm for Trump. Other journalists didn’t see it because they weren’t visiting those counties.

A couple of things other journalists had been missing in my state, leading up to that drive: Pennsylvania, since 1996, since Bill Clinton’s second election, had become more Republican in every presidential race. Typically, analysts just look at the result, not what’s changing. They say, “Pennsylvania’s blue. Next.” But in 1996, Bill Clinton won the state with 28 of the 67 counties. By 2012, Barack Obama won 13. Also, since 2006, I’d observed that the Democrats who were winning elections were moderate, pro-life, pro-gun, fiscally conservative, pro-military Democrats.

In 2016 I identified 10 counties that needed only 2,000 more votes than they gave Mitt Romney to go for Trump. My research suggested that those counties were going to flip. And if they flipped, it didn’t matter what happened in Philadelphia. It didn’t matter if Hillary Clinton hit Obama’s numbers, it didn’t matter if she exceeded them. Which, by the way, she did. I said that if these 10 counties flipped, Trump’s going to win Pennsylvania by about 40,000 votes. I was off by 5,000. And I also believed that if Pennsylvania went for Trump, so would North Carolina, Florida, Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa and Ohio. Why? Pennsylvania is five points more Democrat than all of those states. So in July of 2016, I essentially said, “This race is over, nobody knows it yet.”

Did it help that the area you were researching was your home state?

If you were sitting at home watching this 2016 election cycle on the national networks, what you tended to see in 2016 was the same sort of clip on every channel. You would see two or three awful Trump supporters, and seven lines that Trump said that were absolutely ridiculous. And you said, “This is never going to happen, because his people are crazy, and so is he.” But that coverage came from national reporters who flew in and arrived at rallies 10 minutes before Trump took the stage. And your natural instinct as a reporter is to interview the oddities who stand out. The angry loudmouths.

But I’ve always lived in Pittsburgh, the Paris of Appalachia. The Scottish-Irish side of my family has been in Pennsylvania since 1638. That gave me a unique perspective. When I cover politics, I don’t fly. I only take back roads. I stay in a bed and breakfast. That’s why I had a different take. Not because I like him, not because I wanted him to win, but because I would arrive in a town a couple days before a rally, get to know the people and go with them to a rally five hours before it began. They’re with their family, they’re playing music, they bring food and the soccer chairs that they use when they go to see their kids and their grandchildren play a sport. And it’s a real sense of community. For the most part, the people there are happy. They’re not angry. They’re excited.