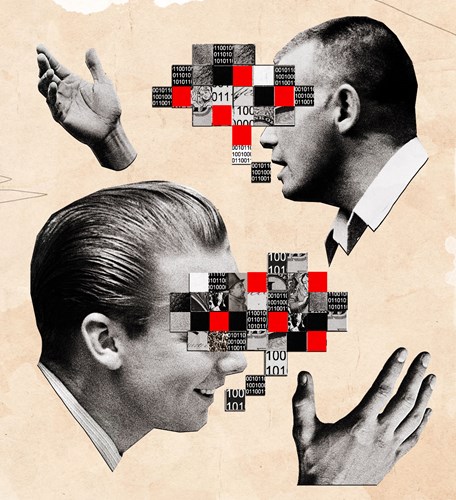

Schroders executives Mark Ainsworth and Ben Wicks on the growing role of the firm’s Data Insights Unit in fund management.

Mergers and acquisitions create some of the biggest challenges that institutional investors face. No matter how practical and potentially rewarding it appears at the outset, the number of variables and possible outcomes around a typical deal can unnerve even the most seasoned fund managers.

The primary way to counteract the turbulence and uncertainty that arises in M&A is through the collection and careful analysis of data, benchmarked against a firm set of metrics that nonetheless molds to suit the situation.

Schroders is a global investment manager, founded in 1804. Schroders’ Data Insights Unit was established in October 2014, bringing together data scientists, consultants and engineers to work alongside traditional investment managers. Schroders believes that data science offers a huge opportunity for active fund managers and that the injection of new methods of data analysis into existing investment processes will enhance long-term alpha generation and generate sustainably differentiated returns.

Brunswick talked to Mark Ainsworth, Head of Data Insights and Ben Wicks, Head of Research Innovation, about how data works in the deal landscape.

Is the data that you gather and analyze helpful in making decisions involving mergers or IPOs?

BW: Yes. A large retailer in Brazil was doing an IPO, and we conducted a very rapid analysis on the level of local competition it faced. We were able to show what percentage of its stores faced local competition today versus a year ago, versus the year before that, and so on. Our information – all of it publicly available but requiring specialist skills to gather and analyze efficiently – tipped us toward not investing in the IPO.

Or let’s say a large retailer says, “We can get to 2,500 stores by 2022.” Is that a reasonable number or a gross exaggeration? Something we can do very effectively is to take a country and analyze how many locations, realistically, are available to a franchise, based on inputs about whether that franchise belongs in shopping centers or high streets or where the local competitors are that they’re targeting. Once we all agree on the inputs, we can run it through and say, “Yes, you can see two and a half thousand locations.” Or maybe we can’t find that. Then we have reason to doubt the overall prospects.

Weren’t you able to provide some insight into the Ladbrokes/Coral acquisition?

MA: At that time Schroders actually owned a large position in Ladbrokes. So when the merger was announced, we needed to know fast what to think of it. One of the key gaps in knowledge was how many stores UK regulators would allow them to keep post-merger, because they were both large players in the market. Together they had about 4,000 stores. The key criterion for regulators is the effect on local competition.

The range of estimates out there for how many stores would have to be divested was between 100 and 1,800. In fairly short order, we were able to find the locations of all the betting shops in the country, and the proximity of shops that UK regulators would likely allow. Calculating the distance of every betting shop to every other betting shop in the country involved about 73 million calculations, far beyond what is feasible on Excel.

Using publicly available data, we concluded Ladbrokes would have to divest about 400 stores, out of 4,000. So the combined company would be 10 percent smaller than before. That’s information – with logically derived precision – that other investors didn’t have. About a year later, the authorities came out with initial estimates of how many stores they would be required to sell, and their number was between 350 and 400 stores.

We have more recently worked on modeling the impact of further regulation in the gaming sector, such as limits on the use of slot machines, with similar success, as well as the potential for deregulation of sports betting in the US.