Unforeseen crisis drove Mark Palmer's high-flying employer into bankruptcy, erasing much of his networth. Then came the investigators. Now a Brunswick Partner, Mr. Palmer endured an experience that was dark even by the standards of COVID-19.

On October 25, 2001, the phone rang on the desk of Mark Palmer, Vice President of Communications for Enron. The caller was a Wall Street Journal reporter inquiring about an Enron special-purpose entity called Chewco.

“Never heard of it,” said Mr. Palmer. Promising to look into Chewco, he said he would get back to the reporter.

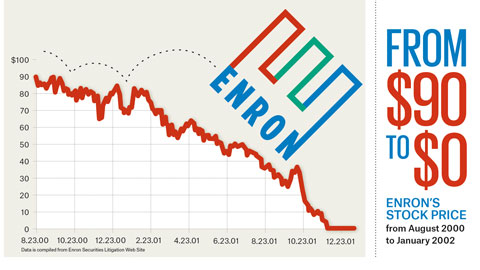

During his first five years as Enron spokesman, Mr. Palmer had scrambled to accommodate ever-mounting interview requests from journalists enthralled with the innovation, the boldness and the incredible growth of Enron. During that time, the value of Enron stock more than quadrupled to $90 a share.

But 2001 brought a series of setbacks: Short sellers planted skepticism in the media, the company’s charismatic CEO abruptly resigned and Enron took an unexpected $1.2 billion charge against equity. The stock sank to below $20 a share.

As he set out to gather information about Chewco, Mr. Palmer still believed in Enron’s capacity to recover. He still believed in the leadership of Kenneth Lay, the company’s long-time chairman who had recently re-assumed the title of CEO. As for Chewco, Mr. Palmer expected to get a quick answer and move on to his next task.

But within moments, he learned from an Enron executive that Chewco might be a deeply flawed entity. Enron executives investigating the files of Andy Fastow, the company’s recently departed CFO, were finding that Fastow might have improperly structured Chewco to circumvent accounting rules and enrich himself. If this suspicion were true, Chewco’s obligations would turn into Enron debt, further destabilizing the company’s finances and destroying what was left of its reputation. The news floored Mr. Palmer.

Exercising an authority that he arguably didn’t wield, Mr. Palmer called for an immediate gathering of top management, including Mr. Lay. So distraught was he that on the way to that meeting Mr. Palmer made a detour to the bathroom to vomit, a delay that cost him a seat at the meeting he had called. So Mr. Palmer sat on the floor of a small crowded conference room. During the meeting, when Mr. Lay failed to immediately grasp the Chewco implications, Mr. Palmer took charge by loudly slapping his hand on the floor. “I’ll tell you what’s going on, Ken,” Mr. Palmer shouted at the Chairman and CEO. “The Wall Street Journal knows more about what’s going on at your company than you do!”

Then Mr. Palmer demanded, as he had before, that Enron hire an independent investigator. This time Enron followed his advice.

Almost twenty years later, Mr. Palmer is a Brunswick Partner and Head of the Dallas office, where he offers advice on a range of topics, most notably how to navigate a corporate crisis. To that discussion he brings a degree of firsthand experience that he wouldn’t wish upon anyone. The son of a Vietnam War Navy attack pilot, Mr. Palmer grew up believing that hardship should be embraced, tackled and internalized, rather than just talked about. But the trial he endured as chief Enron spokesman during its spectacular rise and scandalous fall convinced him that Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is a real affliction. Ever since that episode of nausea in the Enron bathroom, his gag reflex has been oversensitive. “Before Enron, I could have been a sword swallower. Ever since Enron, if I get just a little bit stressed my gag reflex is hypersensitive,” he says.