In India, cash is king – but, it is on notice

In November 2016, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi signed an executive order that removed 86 percent of bank notes in circulation – more than 22 billion notes in total. It was a bold move, given that the economy largely runs on hard currency; in India, cash accounts for 78 percent of all consumer payments by value.

With his signature, Modi simultaneously looked to rid India of off-the-books, illegal wealth and help modernize the economy.

For India’s financial services technology industry, or FinTech, Modi’s intervention was welcome. FinTech encompasses a swath of products and services, from digital payments to insurance. Less cash in circulation bodes well for the sector, creating greater demand for mobile payment apps and digital wallets.

Venture capitalists, who had pumped money into FinTechs for years, had become more conservative in 2016 – investments in the sector had fallen nearly 75 percent in the space of a year. This capital drought had pushed FinTechs to collaborate with the very institutions they had been trying to unseat – established banks.

While seemingly unlikely, the partnerships were mutually beneficial. FinTechs brought speed and agility, a focus on product design and customer experience, and fresh thinking. Banks contributed their massive scale and reach, rigorous compliance and back-end processes, and the credibility that comes from being around for decades. Not all partnerships were harmonious; some banks have complained about a lack of security among some startups.

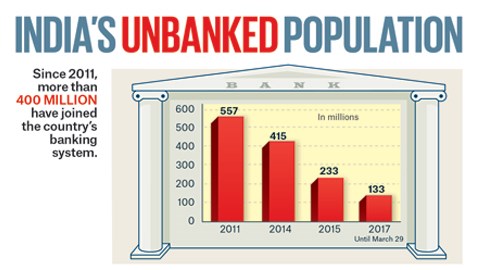

The FinTech sector is being reshaped in part as a result of significant structural reform and modernization in India’s banking system as a whole. India’s unbanked population has been drastically reduced, to around 133 million at latest count, down from 415 million in 2014.

New categories of financial institutions are part of this reform effort. “Payment banks,” for example, officially began operating in early 2017. These are essentially stripped-down versions of a bank, reaching customers mainly through mobile phones rather than physical branches. The recipients of payment bank licenses hail from a range of sectors, including micro-finance, telecoms and online payments.

Government-sponsored platforms – some of which build on the national biometric identity system, Aadhaar – allow for easier online payments and money transfers, helping to create a strong infrastructure to support India’s FinTechs, while fostering financial inclusion.

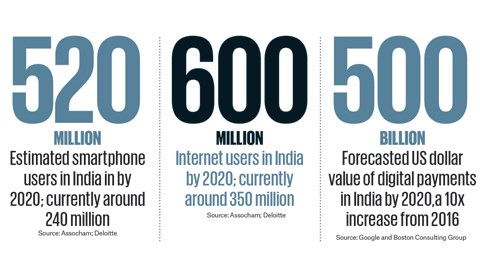

Behind all these changes are broad trends in increasing digital connectivity. By 2020, the number of smartphone users will more than double, and an additional 250 million Indians will be able to access the internet, according to research by Deloitte. As they go online, projections suggest that their payments will as well: Google and Boston Consulting Group forecast digital payments will grow tenfold by 2020.

Yet for all of the strengths of this new service landscape, FinTech is still in the early stages of developing its market (see “India unplugged,” Page 46).

For a start, India has a long way to go before it consigns cash to the history books. Two-thirds of India’s 1.3 billion population are under the age of 35; they will remain reliable early adopters of tech innovations. But India as a whole remains a stubborn user of cash. An initial spike in the number of digital payments followed Modi’s purge of high-value bank notes, but then the volume of online transactions fell back in early 2017, as new notes replaced the old ones.

Building trust in the security of digital transactions will be a big step in weaning India off cash, but a number of high-profile cyber incidents have hampered that effort. In 2016, 3.2 million bank debit cards had to be blocked or recalled after a breach. From private sector start-ups to large government agencies, those responsible for data will need to be better prepared for the fallout from such incidents, and do more to educate employees and customers on how to avoid them in the first place.

Regulation will also need to keep pace with change. So far, the approach has been to do as much as possible to enable the domestic FinTech industry to blossom, especially in the payments space. Other areas, such as disbursing loans, peer-to-peer lending and blockchain, are more complex and will require firms to engage regulatory bodies in a conversation about the rules needed for effective governance.

Finally, whether competitors or collaborators, newcomers or incumbents, organizations will need to be prepared for the next disruptive innovation or bold idea. We can be certain Modi’s assault on cash isn’t the last word.

Azhar Khan is a Partner in Brunswick’s Mumbai office.

Photograph: Hindustan Times, Getty