Music’s secret power offers humanity a bridge through time. Brunswick’s Carlton Wilkinson talks to entrepreneurs, engineers, artists and administrators of three projects in three countries calling the tune for listeners hundreds of years hence.

Can a musical performance last forever? Or even just, say, a thousand years?

On its face, the idea of creating a structure that reaches past the shuffle of this mortal coil seems itself timeless: the Egyptian pharaohs built elaborate temples and tombs, and had themselves buried with treasures and even ships that they wanted to take with them into the next world. The engineers and masons who began the great cathedral of Notre Dame knew they would not live to see the project’s completion.

Those projects, designed to last centuries, had the advantage of fitting in with religious beliefs of the day, demonstrating faith by building something that seemed to surpass the limits of human capacity.

Inspired by the turn of the millennium 17 years ago, a select pool of artists, engineers and entrepreneurs are giving that age-old problem a more practical, 21st-century twist: to open a channel that will allow us to interact with a future many generations hence, spanning the distance from here to humanity’s farthest horizon.

Three different projects – each in its own way – are playing compositions to the distant future and inviting anyone around at the far end to sing along.

The big picture

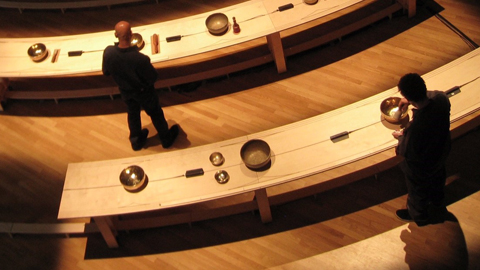

Conceptual artist and composer Jem Finer, who was also co-founder of the Irish folk-punk band The Pogues, crafted a non-repeating piece using a relatively simple algorithm. Titled Longplayer, its computer-guided performance has already started – but don’t worry about coming in late. It began December 31, 1999 and will continue for the rest of your life, your children’s lives, their children’s lives and so on, for roughly 40 generations, before finally ending on the same date in 2999.

One thousand years of continuous performance – the only requirement is that some representative of humanity survives to maintain it.

“It’s easy to think about how to create an artificial intelligence that would keep Longplayer playing,” Finer says in a recent phone interview. “But I’m more interested in getting humans to work together to keep it going. I like the idea that people have to collaborate. In this case, most of the collaborators aren’t born yet and some of them won’t be born for 900 years or more.”

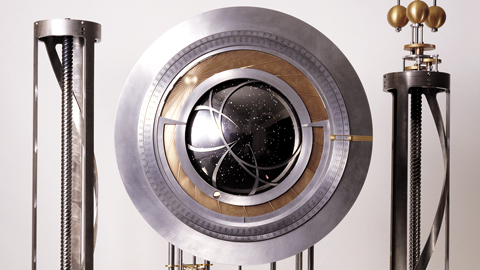

Similarly, a performance of John Cage’s Organ 2/ASLSP – a 1987 piece for solo organ designed to be played “as slow as possible” – could involve multiple generations of performers. A current interpretation can be heard at a medieval church in Halberstadt, Germany – or at least, one chord. The concert began in 2001 and is to last 639 years. Each tone or simultaneous combination of tones is sustained, sometimes for months or years. The last time the notes changed was in October 5, 2013; the next change isn’t due until September 5, 2020. These events are treated like astronomical alignments, attracting a crush of tourists to the small town.

“At the last chord change in 2013 there were 1,500 people from all over the world in Halberstadt,” says Rainer Neugebauer, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the John Cage Foundation in Halberstadt, a small city of 43,000 people. “The whole town was overbooked.”

The Halberstadt church has an earlier place in music history: in 1361 it became the site of the first organ with a modern keyboard, consisting of keys arranged in what we now think of as the standard configuration – 12 keys in an octave, black keys shorter and raised slightly higher than the white. That was 639 years before the year 2000. The Halberstadt ASLSP performance was to begin in 2001, and so the organizers chose 639 years as its length – a way of honoring the site of the invention of the modern keyboard and propelling the town’s keyed history into the unforeseeable future.