McKinsey’s Dominic Barton tells Brunswick’s Kevin Helliker how long-term investing gives companies a competitive edge

Dominic Barton runs six marathons or half-marathons a year, a regimen that requires constant training. At least four days a week he logs six or seven miles, despite traveling about 270 days a year. Within a few minutes of departing a plane, he likes to don his sneakers and hit the pavement, finding that it re-energizes him. He’s not pursuing athletic prizes. Research, Barton knows, shows that runners tend to live on average three years longer than non-runners.

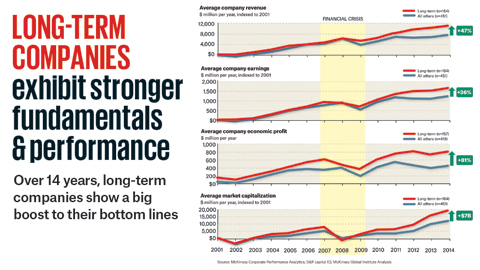

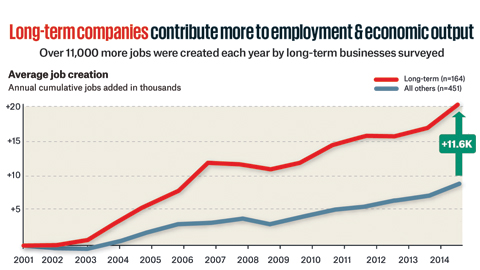

As Managing Partner of McKinsey, Barton stands out as an authority on long-term benefits. He is lead author on a 2017 McKinsey Global Institute research paper showing that companies that are managed for the long term post extraordinary growth in earnings, revenue and market value. That conclusion emerged from his study of the performance of 615 non-finance companies from 2001 to 2015. On average, long-term companies in the study increased revenue by 47 percent more than others in their industry group, and earnings by 36 percent more.

The research put meat on the bones of an argument many business leaders have been advancing for years. “Finally, Evidence That Managing for the Long Term Pays Off,” read the headline on a Harvard Business Review article about Barton’s study.

Of course, it isn’t for lack of such evidence that many executives manage for the current quarter. Their financial incentives often are based on meeting short-term goals. Their job security may be based on that too, in a climate where analysts and investors apply pressure on companies to match or exceed Wall Street’s quarterly earnings expectations. So Barton has no illusions that McKinsey’s research will induce an immediate, massive change in corporate behavior. He knows that chief executives generally aren’t proud of decisions to cut research and development spending in order to satisfy the Street’s demands of the moment.

But the stakes are too high to stop pushing for reform. Managing for the short term has played at least an indirect role in rising income inequality, rising populism, rising unemployment and growing distrust in business, Barton believes. Calling for “a shift from what I call quarterly capitalism to what might be referred to as long-term capitalism,” Barton said in a 2011 HBR article that “we can reform capitalism, or we can let capitalism be reformed for us, through political measures and the pressures of an angry public.”

As a consulting firm, of course, McKinsey doesn’t generally advise clients how to maximize profits during the current quarter. Instead, the firm analyzes deeper, longer-term questions. That emphasis prompts some critics to suggest that Barton’s arguments and research in favor of managing for the long term may be self-serving. But his views are mirrored by industry titans from Warren Buffett to Lord Jacob Rothschild.

For their study, Barton and his co-authors devised an index of five quantitative indicators to identify long-term from short-term management strategies or orientations, relative to their industry peers. The indicators include how much investment a company makes, whether it utilizes accounting decisions to boost earnings, whether it repurchases shares to increase earnings per share and sustainability of margin growth (that is, cost-cutting), and whether it engages in “quarterly targeting.”

Of the 615 companies Barton and his co-authors examined, only 164, or about 27 percent, engaged in what he calls long-term capitalism. But he expresses hope. “People are listening and momentum is building,” said Barton. In a phone call from Lisbon, Barton discussed with the Review his thoughts and research on long-term capitalism.