Mark Beaumont was on course to break a world record when suddenly his boat capsized, he talks about the management lessons he learned while trying to survive

It was 10:55am and i was rowing hard in the final five minutes of my shift. Ian, as always, was in front of me, Yaacov behind, and we were going fast, just over 500 nautical miles from our destination in Barbados. The swell and winds were coming from the east and it was a large but fairly predictable sea. My thoughts were on what I was going to eat during my two-hour break and I was looking forward to a short sleep, too. None of us had slept for more than 90 minutes at a time in the 27 days since we had set out from Morocco.

Despite huge fatigue after four weeks of very hard rowing, spirits were high. The trade winds had finally reached us and for the last 48 hours our speed had picked up considerably. We were tantalizingly close to world record pace – just another six days.

I didn’t see or hear it coming. Sara G [the boat] pitched up without warning, the stern cabin in front of me lifting quickly as a large wave sped under us. There was an awful moment in equilibrium as we perched perfectly on our side. I can’t remember much except I was then upside down, in the water and fighting to get my shoes out of the rowing straps.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. With both hatches open for those few minutes during the change of shift, both cabins were flooded and there was no chance she would right herself.

Holding on to her upturned hull, we had very little time to act. If she went down before we set off an emergency beacon or salvaged a life raft then our chances of survival were nil.

Swimming around in high seas hundreds of miles offshore gives you a new perspective. I had been in serious scrapes before. This was the first time I thought I was about to die.

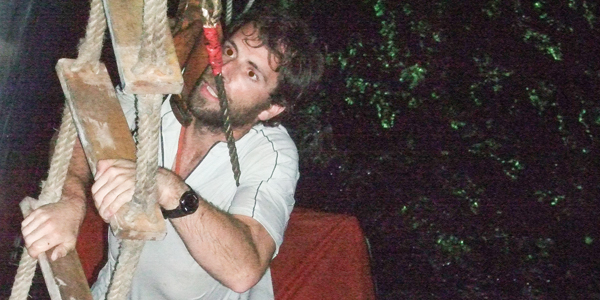

Salvaging the raft wasn’t easy. It was in a hatch on the rowing deck of the boat, which was now upside down and an air pocket held it firmly in place. It took Aodhan, Matt and me nearly 20 minutes to wrestle it free.

We counted the small blessings. It was daylight, and being so near the Caribbean, the water was fairly warm. Even so, after so long treading water and holding on, I was shaking with cold.

It was clear that to get rescued quickly would mean going back to Sara G to find other emergency equipment. During the afternoon Matt and I made return trips, swimming the 50 meters between the life raft and our upturned vessel, while the other four in our crew waited in the life raft.

I wasn’t confident about holding my breath long enough to do anything useful as I dived underneath the boat, squinting to see clearly in the salty water. Finding anything useful was difficult in that dark, flooded, upside-down world. The first time I resurfaced I brought with me a fire extinguisher! The next trip was more successful when I broke the surface holding a GPS tracker beacon. This was the lifeline we needed – rescuers would now know exactly where we were.

The last trip back – to find the desalinator and satellite phone – was, by far, the worst. The line was constantly slack from the swell and I fought to keep my head above water. The relief when I reached the raft was immense, and once aboard I immediately had to lean back out to be sick after all the salt water I had swallowed.