The jihadist group al-Shabaab banned single-use plastic bags in 2017, an order similar to the kind found today in 90 countries, including a number that have designated al-Shabaab as a terrorist organisation. If it’s true that a common danger can unite enemies, it’s difficult to think of one as unifying as plastics.

The problem has appeared in both liberal and conservative publications, and been decried by political parties in the US and UK seemingly incapable of agreement. The Guardian summarised the situation last year: “a worldwide revolt against plastic, one that crosses both borders and traditional political divides.”

That revolt counts among its members a widening body of regulators, consumers, investors and activists, who broadly agree with two points. First, that the world is producing—and discarding—too much plastic. And second, that something needs to be done. There is debate about what needs to be done exactly, and how it should be undertaken, but most agree on who needs to be leading the effort: businesses.

The discussion about plastics often focuses on a product—like bottles or bags or straws—but tends to spark much larger questions about the role of business in society and its responsibility in tackling issues like responsible consumption and climate change. The ubiquity of plastic means those questions are being asked in most every sector and geography.

That plastics are both useful and inexpensive incentivises companies to continue using them, yet those same features also make plastics an issue where companies can demonstrate they are putting principles—and the planet—ahead of profits.

Yet the pull of inertia and inaction is strong. Plastic is a global, systemic problem, making an individual business’s efforts seem inconsequential, while the costs of their efforts are often substantial.

But leading companies are increasingly stepping up to be part of the solution – to protect their short-term licence to operate, and to develop more sustainable products and smarter processes for the long-term. Corporate responses are taking different forms, but most follow a similar pattern: identifying where they can make the greatest contribution, and then working through their spheres of influence to make a systemic impact that benefits consumers, shareholders, and the environment. These efforts have led to more innovative products being created and sometimes new ones altogether, and they’ve built stronger relationships with stakeholders and bolstered their reputations. Implied in these initiatives is a recognition that the problem of plastics, much like the material itself, isn’t going away any time soon.

The Problem in Two Charts

In 2015, the year for which the most recent data is reliable, the world produced 381 million tons of plastic, which UN Environment estimates is equivalent to the weight of the entire human population. The main producer of plastic is packaging, which generates more than 141 million tons annually—nearly double the combined production of the textiles and consumer industries.

Source: Our World In Data

Most of that plastic isn’t recycled—91 percent, in fact, according to a 2018 estimate by Great Britain’s Royal Statistical Society. That 91 percent either gets incinerated—the US, for example, burns six times more plastic than it recycles—or discarded. And that discarded plastic, whether it winds up in landfills or oceans, will be there for centuries. It takes straws 200 years to biodegrade; plastic bottles 450 years, and fishing lines 600 years.

Of growing concern are microplastics. Plastics break down into smaller and smaller pieces, and as they do, they end up in marine life, in the air, and in our bodies. “Microplastics have been found in every part of the world, from Mount Everest, its highest peak, to the Mariana Trench, its deepest trough,” the Intercept reported in 2019.

Source: Our World in Data

The pace of plastic production has accelerated sharply. Half of the plastic ever produced was made in the last 13 years. It is becoming cheaper to make plastic and emerging markets are expected to consume more plastic, meaning production is likely to keep rising. As it does, so will plastic waste. Global plastic-waste volumes were 260 million tons in 2016; McKinsey estimates that it could be 460 million tons by 2030. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation has warned that by 2050 there will be more plastic than fish in the sea.

Why is so little being recycled? Partly because the global recycling system has, according to the FT, “stopped working.” In December 2017, China, which had long received most of the West’s recycling waste, announced it would no longer accept imported recycling. This affected both the economics and capacity of the world’s recycling industry. A decline in both has meant that more plastic than ever is being burned or sent to landfills. China’s decision was a tipping point, but The Intercept reported that “the plastics problem has been with us as long as plastic has.” Not all of the seven main types of plastic can be recycled. Almost 80 percent of plastic that’s ever been produced has gone to landfills or been discarded—at its peak recycling rate in 2014, the US recycled less than 10 percent of its plastic.

Who’s Paying Attention to Plastics?

Pretty much everyone.

The documentary series Blue Planet II was the most watched TV event in the UK in 2017, attracted more than 80 million viewers in China, and has since been streamed on Netflix in 190 countries. Its jarring footage—a sperm whale trying to eat a plastic bucket, an albatross poisoned by plastic—is widely credited with sparking global outrage. Kim Kardashian, a celebrity with more than 220 million followers across social media, posted about plastics and implored her followers to “care enough to fix it!” The topic has appeared on the cover of tabloids and leading science publications, and BBC One has run a series called War on Plastic. Since September 2019, one news aggregator collecting media coverage about plastics has tallied pieces from The Guardian, Reader’s Digest, Reuters, Time, Business Insider, CBC, and the Scientific American, among others.

Research in 2019 found that more than eight in 10 consumers were “very concerned” about plastic, while a separate study found half of UK consumers “would be willing to pay higher prices for eco-friendly packaging.” The same study found overwhelming majority in favour of government action: Mandating more eco-friendly packaging, requiring companies to charge for plastic bags, and a deposit return scheme for bottles.

Governments are increasingly taking those kind of steps. Almost 30 countries have enacted some type of ban on single-use plastics—either on specific products, materials, or production levels. More than 60 countries have enacted Extended Producer Responsibility measures, such as product-take back schemes, deposit fund, and waste collection and takeback guarantees – all aimed at putting manufacturers and retailers on the hook for where their plastic products end up.

With harsher taxes and regulation looming, more asset owners and managers are viewing plastics as a business risk. The asset management arm of the Bank of Montreal, which has $240 billion in assets, asked 27 companies to take steps to reduce plastic, recycle more, and redesign their packaging. Schroders, an asset manager, has sought information from 100 companies about their plastic consumption and usage. The Plastic Investor Working Group, comprised of nearly 30 global investors and convened by the UN Principles for Responsible Investment, whose signatories have almost $90 trillion under management, are studying the financial future of plastics.

Four Common Solutions—And A Leading One

When people demand that businesses “do something” about plastics, they’re typically referring to one of four steps, or some combination of the four.

-

Reduce the use of plastic packaging and non-recyclable waste. A number of businesses have set ambitious reduction targets and made bold public pledges on this front. Starbucks, for example, announced it would no longer use plastic straws globally by 2020 (it estimated it uses about 1 billion straws a year). Nestle, UK supermarket chains Waitrose and Sainsbury’s, and international cruise lines and hotel chains have also pledged to drastically reduce single-use plastics.

-

Replace plastics with new biodegradable substitutes. This includes compounds made from algae, plants, sawdust and even sugar. At present, these lack scale to be meaningful: Global bioplastics production capacity was 1 million tons in 2018 (remember, global plastic production was 381 million tons in 2015). By 2023 that bioplastic production is set to increase only to 2.6 million tons. Another challenge is that these products tend to be more expensive, require more fuel to produce, and struggle to match plastic’s usefulness. A substitute which doesn’t keep food hygienic as long as plastic does, for example, may lead to increased food waste.

-

Recycle materials and help customers do the same. Nespresso, a company that sells coffee makers, offers a service that allows customers to recycle their coffee “pods” that make a cup of coffee. Nike, H&M, and Levi’s all offer to recycle old products, while Adidas went so far as to make the Parley trainer from plastic waste found on remote beaches. However, recycling is considered by some a “least-bad” option. Plastic can only be recycled a limited number of times, and producing new goods from recycled plastic can use significant energy and resources than it takes to simply make new plastic. And not all plastic can be recycled. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimates that without fundamental redesign and innovation, 30 percent of plastic packaging can’t be recycled.

-

Remove plastic altogether; don’t simply recycle plastic, burn it, or bury it. A move for companies and organizations investing in cutting-edge research and solutions. One promising development has emerged in the form of fungi that can break down solid waste. Researchers in Japan have found a strain of bacteria that breaks plastic down into smaller compounds.

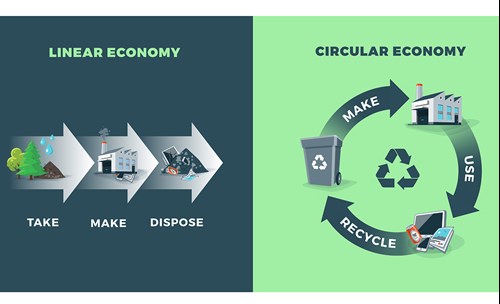

The New Model: From a Linear Economy to a Circular One

Each step on its own marks progress, but collectively they represent a broader shift from a linear economy toward a “circular” one. The linear model is today’s reality: Companies take materials, make products, and consumers dispose of those products when they stop working or want to buy new ones. Waste is inevitable; it’s part of the system’s design. Circular, on the other hand, looks for materials and products to have much longer lifespans. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation breaks it into three core principles:

- Design out waste and pollution

- Keep products and materials in use

- Regenerate natural systems

As simple as those steps sound, they would require a fundamental rethinking and restructuring of how the economy is powered, how products are manufactured and used, and the level of responsibility that consumers and companies have for what they use. But Accenture has estimated that such effort would be worth it, potentially creating an additional $4.5 trillion in savings and value.

A circular economy was once a niche, technical topic, but it’s increasingly become mainstream. The move has been acknowledged by major trade associations like the American Chemistry Council, which has said it’s “embracing the drive toward a circular economy for plastics.” The European Commission has a Circular Economy Action Plan, London’s Mayor Sadiq Khan has pledged to “take a circular economy approach” to the city’s resources.

And businesses are embracing it as well. The fashion company H&M has pledged a “100% Circular & Renewable” ambition, while Philips CEO Frans van Houten has said that “for a sustainable world, the transition from a linear to circular economy is essential.” The Ellen MacArthur Foundation has helped organise the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment, which more than 350 organizations have signed since October 2018 with a goal of creating a “circular economy” for plastics.”

So What Can Businesses Do?

Assess your plastic footprint

Recognize your plastic footprint and see how it can be improved, whether that’s in your direct operations or across your value chain. Coca Cola worked with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation to map and publish its annual plastic usage. More than 250 organisations that represent 20 percent of all plastic packaging have pledged to eliminate plastic waste and pollution at the source. Unilever is cutting its use of new plastics in half by 2025, and collecting 350,000 tons of plastic for recycling.

Focus on Sector-Wide Partnerships that can drive Systems Change

Systemic problems—of which plastics is certainly one—require systemic solutions. As businesses address their own footprint they can also look to amplify it by joining with partners to tackle the problem at scale. Through its “Systemic Initiatives,” for example, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation brings together leading businesses, governments, philanthropists, innovators, NGOs, and citizens to help address the plastics problem.

The Closed Loop Fund, which has backing from many of the world’s largest consumer goods companies and family offices, is focused on building the circular economy. “We are reimagining the current linear system, in which billions of dollars are spent annually to landfill valuable commodities,” the Fund writes, “to create circular supply chains that reduce costs, generate revenue, and protect our environment.”

Bunzl, a FTSE100 company that distributes essential products for businesses, is working with its “customers and suppliers to lead the industry towards a sustainable approach to single-use plastics” – a powerful example of using commercial relationships to drive change.

Raise Your Voice as an advocate for change

Leaders like Philips’ Frans van Houten are using their profile to raise awareness about the issue and advocate for collective action. Some companies are going even further and aligning their advocacy in a more literal sense: In 2019, both Coca-Cola and PepsiCo left the Plastics Industry Association, a trade group that had a history of lobbying against regulation on plastic. In a statement, Coca-Cola cited “positions the organization [Plastic Industry Assocation] was taking that were not fully consistent with our commitments and goals.”

A third component is “learning out loud,” or being transparent about the scope of the problem, the difficulty in overcoming it, and sharing what’s working—breakthroughs in developing new materials, for example—and what isn’t. Earlier this month, IKEA CEO Jesper Brodin acknowledged that the company, widely praised for their efforts on sustainability, was “still having internal debates over the fear of greenwashing.” Such candor demonstrates that your priority is on solving the problem, not managing a reputation.

The sequencing and steps will vary for each business, but what is likely to remain constant is the expectation that they take action of some sort. “It’s a big transformation,” Mr. Brodin told the FT. “And if you don’t do the transformation, it will be game over.”