The celebrated author, academic and feminist speaks with the Brunswick Review

As one of western literature’s oldest surviving stories, The Odyssey boasts a number of firsts. It offers the first example of literary sarcasm as well as the first mentor – in the form of a character actually called Mentor. According to Mary Beard, the epic poem has another “first” to its credit: the first written record of a man telling a woman to shut up.

The woman being silenced is Penelope, a wife grieving for her missing husband. The man telling Penelope to “go to thy chamber and mind thy own housewiferies” is Telemachus, her son. Why does an exchange composed nearly 3,000 years ago matter today? Because, as Ms. Beard writes in her best-selling Women and Power: A Manifesto, “When it comes to silencing women, Western culture has had thousands of years of practice.”

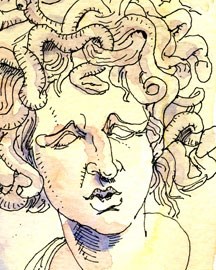

To make that case – and Ms. Beard does, forcefully – she mines mythology and history, and examines a cast of characters ranging from Aristotle to Angela Merkel, Medusa to Margaret Thatcher. Ms. Beard’s writing has the dexterity and confidence that comes with being, as she’s often described, the world’s greatest living classicist. A professor at Cambridge, she makes regular appearances on talk shows in the UK, her op-eds appear in major newspapers, and she has presented documentaries on the BBC. An increasingly popular T-shirt reads: “When I grow up I want to be Mary Beard.”

Ms. Beard’s following stems not only from what she says, but also how she says it – an academic rigor combined with a refreshingly un-academic tone. In a recent interview with The Guardian, she equated the uncertainty around the UK referendum vote with “wanking in the dark.” In a 2018 blog titled “Why Classics Matter,” Ms. Beard described members of the Alt-Right as “spotty adolescents angrily typing out bile after their Mums have gone to bed.” The aforementioned Telemachus is a “wet-behind-the-ears lad.”

I asked Ms. Beard recently what she’d say to her readers – or T-shirt wearers – who are inspired by her unapologetic tone and the quality of her writing on the treatment of women, yet feel they can’t speak up without facing personal or professional repercussions. “That’s hard,” Ms. Beard said. “I would say to them that for years I was silent – but not now. The solution is a combination of bravery and the ability to recognize the words you hear yourself speaking as your own.”

Ms. Beard started lecturing at King’s College, London in 1979. Her first best-selling book came 36 years later, and was the 15th one she’d published, SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. It made both The Wall Street Journal’s and The Economist’s “books of the year” lists, and was one of The New York Times’ 100 notable books of 2015. Her 2008 book on Pompeii led to Ms. Beard’s first appearance on the BBC, presenting a documentary on the ancient Roman city.

In Women and Power, Ms. Beard wrote about the grotesque responses she still receives after appearing on TV: “a load of tweets comparing your genitalia to a variety of unpleasantly rotting vegetables.” A.A. Gill, the deceased TV critic, wrote in 2012 that Ms. Beard was “too ugly for television” and “should be kept away from the cameras altogether.”

Ms. Beard’s response to Mr. Gill appeared in the Daily Mail: “There have always been men like Gill who are frightened of smart women who speak their minds.” She went on: “Maybe it’s precisely because he did not go to university that he never quite learned the rigour of intellectual argument and he thinks that he can pass off insults as wit.”

When responding to tired criticism that focuses on her appearance rather than her ideas, Ms. Beard’s tone can be wonderfully acerbic. But when building a case that women have been silenced and marginalized for millennia, and that the effects of this still linger – more than we might be comfortable to admit – Ms. Beard’s approach is measured and restrained, and resists oversimplifying history or reducing it to a tidy set of simple lessons.

“Western culture does not owe everything to the Greeks and Romans, in speaking or in anything else (thank heavens it doesn’t; none of us would fancy living in a Greco-Roman world),” Ms. Beard argues in Women and Power. But many of our ideas about leadership and the qualities that underpin it “still lie very much in the shadow of the classical world.” And the classical world was unquestionably a masculine one.