Trying again, she said, “As a New Yorker, how does it make you feel to see Herald Square this empty.”

That did it. “Actually, I’m from Kansas City,” I said.

“Excuse me?”

“KC,” I said, tipping my Chiefs cap for emphasis.

Her eyes, drifting beyond my shoulder, implored some other stranger to come rescue her.

I walked away scolding myself. “What the heck was that about? Your wife is a New Yorker. Your daughter was born at NYU. You’ve lived here for eight years.”

But I was unrepentant. “She shouldn’t have called me a New Yorker.”

This beef of mine was particular to New York. While living in Chicago, I’d called myself a Chicagoan. During two stints in Dallas, I’d worn cowboy boots. Like Kansas City, however, Chicago and Dallas belonged to what New Yorkers called flyover country.

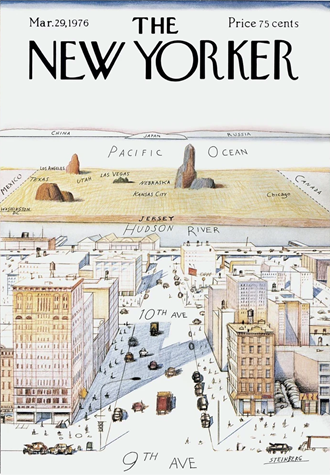

Thirty years ago, when I joined the Wall Street Journal in Dallas, I discovered that my counterparts in New York felt a bit sorry for me. They just assumed I wanted to live and work in The Only City that Matters. In every New York apartment I visited, there hung that Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover, belittling everything west of the Hudson River. I met New Yorkers ashamed of their Midwestern roots, New Yorkers who couldn’t fathom anyone choosing any place else, New Yorkers who’d attained one of their highest goals in life once they’d moved into a dingy studio costing thousands of dollars a month.

I went the other way. For 20 years I worked in the WSJ’s Dallas and Chicago offices, declining promotions that would have brought me to New York, accentuating my Kansas twang whenever I spoke with particularly proud New Yorkers, sometimes acting dimwitted in honor of the smartest business executive I’d ever covered, the late Sam Walton. As a journalist, meanwhile, I wrote stories about important and interesting people in places New Yorkers generally considered unimportant and dull. Out of Kansas City alone I logged more than 200 bylines.