Background

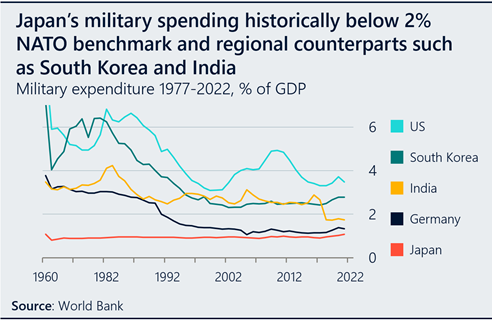

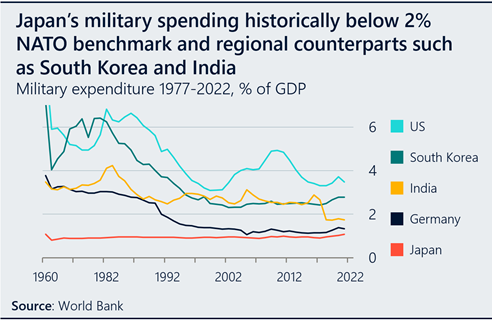

At the end of World War II, the US government devised and implemented a pacifist constitution for Japan that limited the country’s military. After recent reinterpretations of the constitution, Japan has officially declared that Japanese military capabilities are critical to protecting the Japanese homeland, maintaining peace and promoting international order.

On December 16, 2022, the government of Japan released three major national security and defense-planning documents: the National Security Strategy, the National Defense Strategy, and the Defense Buildup Program (DBP). Their impact, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida explained, will be to double Japanese defense spending by 2027.

This change in how Japan understands the role of its security forces is in response to both new and old geopolitical challenges: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, tension between China and Taiwan and the ongoing challenge of North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs.

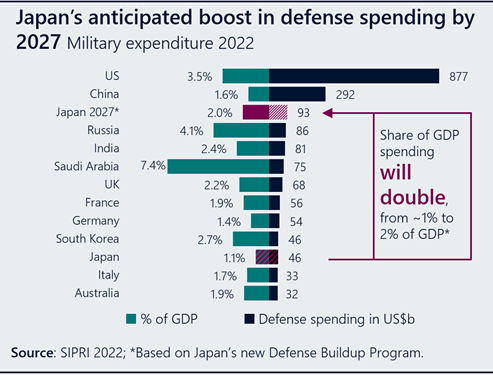

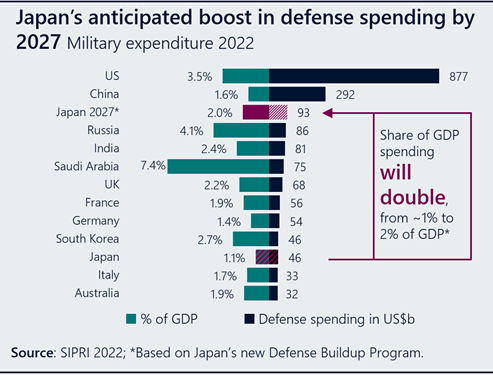

Under this plan, Japan will have the third-largest defense budget in the world by 2027 (Japan currently has the tenth-largest defense expenditure in the world, trailing South Korea, Germany, France, the UK, Saudi Arabia, India and Russia, as well as China and the US). Japan would also become increasingly responsible for its own national security.

Japan is currently the world’s third-largest economy, with a GDP of $4.25 trillion. As Japan’s defense spending stands now, at slightly more than 1% of GDP, this proposed increase is the largest ever by a democratic nation in peacetime, with the exception of President Ronald Reagan’s US defense buildup from 1981 to 1987.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s 2022 defense spending announcement, made in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, aims to bring Germany’s fourth-largest global economy from 1.3% to 2% of GDP spending on defense by 2027. Like Japan, Germany recognizes that current defense spending levels are inadequate, but Scholz’s plan has been mired in challenges, including procurement delays and intergovernmental coalition differences, with increases far below the sums initially announced.

Japan’s Defense Buildup Program and export market

The transformation of Japan’s defense acquisition processes and defense industrial base will be key to Japan’s buildup. These transformations must reflect not only the degrading security environment Japan faces, but also the technological advances in military affairs brought about by IT-enabled and digital-defense capabilities. Japan needs to develop improved intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities; precision-strike capabilities; cyber defense; space defense and directed energy (laser and microwave systems) technologies.

Recognizing the need to fundamentally change defense acquisition, the DBP aims to lure more private-sector interest and entrants by improving the longer-term predictability of procurements, offering subsidies for industrial facilities and cyber defenses and strengthening information and industrial security.

In addition to improving the procurement process, the DBP seeks to enhance Japan’s defense-technology base by tightening deadlines on R&D in line with the country’s acquisition requirements, promoting new R&D initiatives with foreign partners, adopting international requirements (replacing Japan-specific ones) and including nondefense technologies for R&D.

Lastly, recognizing the need for Japan to move to codevelopment and export of defense equipment, the DBP allows for equipment transfers to build international partnerships, which are critical to expanding Japan’s defense industrial base.

Japanese law and practice have inhibited development of the robust defense export market necessary to maintain a sizeable and state-of-the-art defense-industrial base.

Japan’s industrial sector also faces severe demographic challenges. If current trends continue, Japan’s population of 125 million will shrink to 88 million by 2065, presenting challenges to the growth required to sustain defense spending as well as to the country’s ability to recruit sufficiently for the armed forces. Japan will need to become a defense-equipment exporter to benefit from the potential economies of scale that overseas sales afford.

In 2014, Japanese companies Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Kawasaki Shipbuilding engaged in discussions with the government of Australia to export Soryu-class diesel submarines to Australia in a blockbuster $38.5 billion deal.

But the plan fell through when a new Australian government chose France’s Naval Group over the Japanese consortium. Australia said it chose France over Japan for technical reasons, but news reports indicated two additional explanations: First, France had far more experience bidding on overseas defense contracts and placed greater emphasis on job creation in Australia as well as sharing technological prowess; second, the perception in Australia that French submarines would be seen as less hostile to the PRC than Japanese ones. In 2021, Australia chose to abandon the diesel submarine program for nuclear-powered submarines developed through AUKUS, its defense partnership with the US and the UK. But the defeat for Japan was a painful one, and its lessons should be incorporated in future defense cooperation.

In recent years, Japan has begun to export defense equipment more modestly as it deepens defense cooperation and development with allies. Japan’s deep economic ties in Southeast and South Asia, as well as in the Middle East, Europe and the US, offer more potential for defense cooperation and exports.

In 2020, Mitsubishi Electric concluded a contract to develop fixed and mobile air-surveillance radars for the Philippines – the first winning Japanese bid for an overseas defense contract since the 2014 submarine debacle. In October 2022, Kyodo News reported that Japan had announced plans to sell stealth antennas to India.

In December 2022, Japan announced plans to codevelop a sixth-generation fighter jet, the Global Combat Air Program (GCAP) in cooperation with Great Britain and Italy. The lead developer of the GCAP for Japan will be Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, working in close partnership with UK lead BAE Systems and Italian lead Leonardo S.p.A.

Japan’s ability to enhance its own defense-industrial base and technology is critical to the partnership. Japanese officials consciously chose to codevelop equally with the UK and Italy over the US, reportedly due to concerns that Japan would be the junior partner to the US. Production on the sixth-generation fighter, which is being designed for export to Europe and the Indo-Pacific, will begin in 2030, with the first fighter deployed in 2034.

Unprecedented opportunities, major obstacles

This unprecedented increase in Japanese defense spending presents significant opportunities for companies in the defense and security sectors, and for the dual-use technologies that have become critical to these sectors.

But there are also obstacles to be overcome. Japan is known for its leading technical expertise in areas such as robotics, diesel submarine construction, material sciences, amphibious vehicle design and ship-building capabilities. But its homegrown defense sector has been dominated by legacy, specialized, smaller manufacturing firms or by Japanese conglomerates that do not view defense as central to their broader corporate portfolio.

Japan’s longtime ban on the export of weapons and war-fighting capabilities has also limited potential markets for its own defense equipment, hindering coproduction and global partnerships. The ban was eased in 2014 by then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, but almost a decade later, Japan has yet to become a full-fledged entrant in the defense export market.

This challenge is exacerbated by the lack of clear industrial security policies for manufacturing and research facilities, and tight security clearances for the private sector, both of which are the subject of intense and ongoing reform efforts.

While Japanese craftsmanship, R&D and know-how have made Japan a global powerhouse in numerous critical sectors, only 2.4% of the top 100 defense companies worldwide are Japanese.

Navigating Japanese public sentiment

Much of the older Japanese population, raised under the US postwar occupation with its emphasis on pacifism, or in its aftermath, remains opposed to spending on weapons, even for defensive purposes. But geopolitical tensions in the region are shifting that sentiment. Opinion polls conducted for newspapers of varying ideological viewpoints reveal that support for the defense budget outweighs opposition, except in Okinawa where the US base presence has long been a source of controversy. Polling by the Cabinet Office in late 2022, however, showed 41.5% support for the defense buildup, its highest level since 1991, but still a minority. In the same poll, 53% of those surveyed indicated they were content with current defense spending (not necessarily in favor of a decrease).

Subsequent debate over the precise source of funding for the defense increase has added another layer of complexity. A poll by NHK, Japan’s public broadcaster, shows over 60% of the public opposes a tax increase to fund the defense buildup.

In this environment, any large-scale defense-related project could become the subject of harsh public scrutiny. New entrants to the market will require nuanced and strategic communications.

Recommendations for Business

For Japan to make this transformation in an economically sustainable manner, it will need to strengthen defense cooperation with its allies, as well as cooperation on sensitive dual-use civilian-military technologies, to improve its ability to enter the growing global defense market as an exporter nation.

This presents significant potential for growth for business, but it’s a complex and evolving situation. Although the Japanese domestic defense industry welcomes the unprecedented budget increase, it may struggle to accommodate the subsequent increase in demand – production capacity has been kept at a bare minimum for decades. There will be a significant shortage of experienced workers because of the long-restrained market and the impacts of an aging society. Growing pressure on frontline workers to meet the demand will likely lead to requests for greater compensation, increasing overhead costs.

Non-Japanese companies entering the Japanese market could be seen as opportunistic outsiders, or, in the worst case, as avaricious, if they fail to navigate appropriately between public sentiment and the sensitive set of relations between industry peers, government ministries, the policy community and the media. These challenges are magnified by cultural pitfalls that foreign corporate entrants often underappreciate in Japan.

The solidarity of those currently in the domestic defense sector – which has survived in the face of underfunding for decades – should not be underestimated. Proactive engagement by new entrants seeking to influence Japanese politicians could come across negatively in the eyes of local partners (if done without sufficient coordination with peers), which could significantly harm corporate reputation in Japan.

Japan’s policymaking circle also has its own unique ecosystem. For instance, government bureaucracies play a more significant role in driving policy than in the US or even western Europe. The role of business and how it engages with government ministries can be the subject of unfavorable coverage in the Japanese media.

Japan is a demographic with strong social norms and a legacy of lifetime employment. All of this adds multiple unperceived layers of complexity for those bidding on government contracts. It is critical for non-Japanese companies to work with both global and local trusted strategic advisors who can bridge the massive gaps between Japanese stakeholders and “overseas.”

Download a copy of this article here.