Mr. Timms opened the webinar with three stories about how the world is changing—from the medical profession, business and politics. What all those stories illustrate is the idea at the heart of the work of Timms and his co-author, Jeremy Heimans—that the way to think about how the world is shifting is not a shift in technology but a shift in power. It is an emergent and new way to be powerful and those people who are understanding this power are those who are getting out on top.

First, in the medical profession. In 2019, the World Health Organization placed the risk of a pandemic among the top 10 greatest health challenges in the world—and hesitancy to be vaccinated right up there alongside it on that list. One of the interesting challenges we have ahead, Timms says, is “how can the medical profession—which is used to being much more of a top-down command-and-control world—out-communicate a community of people around the world who are decentralized and distributed, creating power in their own ways? There is no boss, no headquarters.”

Wielded by a few, power in the medical community “tends to download,” he said. Prescriptions written in Latin, that only fellow experts understand, are a symbol of that mindset—a closed language about contained power. “How different that is to the new power world,” Mr. Timms says. “The anti-vaxxers are powerful because their power is made by many. It is about what you have uploaded. It is about what you can share.”

In business, Airbnb only exists because of the properties that we place on it. It is very much about the crowd directing the business in terms of the content. In the face of pending state legislation, the company turned not only to its advisors and lobbyists but to its network of guests and hosts in California to mobilize. And through them, knocking on 250,000 doors, Airbnb successfully fended off the regulatory challenge.

In politics, former President Barack Obama’s campaigns are examples of the power of a collaborative network that viewed itself as a movement. “Obama’s presidency itself, the way he governed, was actually very traditional,” Timms says. “All the energy of the crowd that got him elected, he left behind when he got into office. And he essentially handed over that energy to Donald Trump.

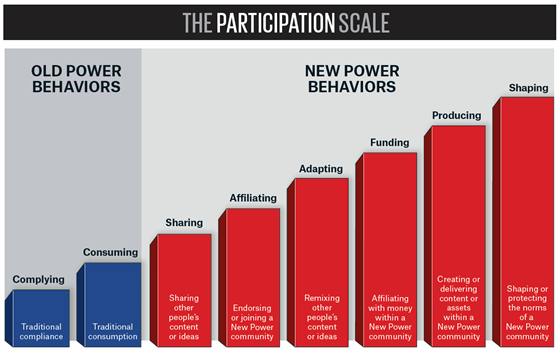

“In the old power world, power is a currency. It is about what you had that nobody else had, that you could cling on to. Versus power as a current: that power which surges and moves and while you can never quite own it, you can direct that power,” he explains.

#MeToo, Black Lives Matter, Extinction Rebellion, social movements that have defined our times, are all new power phenomena. So is the rise of President Trump and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro. “You are seeing much more of these spikes of new power,” he says. “New power is very good at surging up and then disappearing.”

By itself, it can bring progress but also breed chaos, as the mob of Trump supporters inspired to storm the US Capitol in January demonstrated. The conversation with Mr. Timms took place before those tragic events unfolded, but his view was clear-eyed about the need for a balanced approach. “My argument to you is not old power is bad, new power is good,” he said. “That is not the argument.” What we need, he emphasized, are agents who have the right dose of both old power and new power to be able to get ahead. And he warns that that will require all of us to become better citizens.

Taking questions from Sir Alan Parker and the audience around the world, Timms elaborated on these ideas and how they figure into his work with Giving Tuesday and Lincoln Center, and the outlook for corporations around the world. Despite negative uses of new power, he remains decidedly optimistic that its rise is a force that can benefit society.

As the Giving Tuesday concept travels, groups in each country have remade the heart logo used in the US to suit themselves. Being open to such free adaptation is a hallmark of “new power” leadership.