Board members must adapt or risk becoming obsolete, says Spencer Stuart’s Edward Speed

Boards of listed companies are operating under greater scrutiny than ever before, in a political and social climate increasingly characterized by cynicism and a mistrust of business. Directors are exposed and accountable to an unprecedented degree.

Under the weight of legislation, governance codes and listing requirements, it is easy for a board to get bogged down in compliance issues instead of dedicating sufficient attention to strategy and the ability of management to execute it successfully.

Every board has a responsibility to oversee management with active questioning, constructive challenge and support, wherever needed. But to do this effectively, the board has to be agile, engaged, responsive, diverse and above all, relevant.

A board cannot fulfill its responsibilities without deep knowledge of the company and the context in which it operates. That means it needs to keep pace with such things as disruptions to the business model, digital transformation and cybersecurity.

Investors are responding to these pressures by monitoring board effectiveness and calling for more frequent changes in board composition.

These pages show some statistics and trends that define the state of boards today. It is important to note that boards are having to deal with a constantly changing agenda. They are going to have to be prepared to adapt even faster than they have in recent years – or risk becoming obsolete.

SEPARATED ROLES: LEADERSHIP

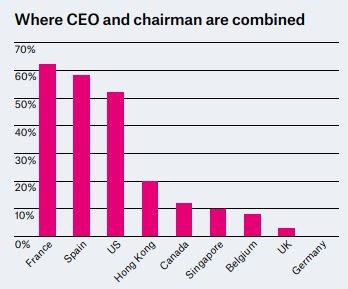

Where CEO and chairman are combined

While there is a global trend to split the CEO and chairman roles, France, Spain and the US are obvious exceptions. Combining the roles can be an effective temporary strategy, as long as the chairman can step back when the time comes. In some countries, such as Germany, governance law requires that supervisory boards be independent of management, so the CEO cannot serve as chairman

The role of chairman has changed in recent years as board work has become more onerous and there is a growing belief that the roles of chairman and CEO are best separated.

First, concentration of power in one pair of hands heightens risk. Board members should always feel free to challenge the CEO’s decision-making process. When the chairman is also the CEO, directors can feel uncomfortable and at a disadvantage – although the presence of a lead director (or senior independent director) can mitigate this problem.

Second, running the board and running the company are two distinct activities, requiring different skills. A good independent chairman will focus on time-consuming board governance issues, freeing the CEO to take care of the day-to-day running of the business.

Boards that promote the outgoing CEO to the role of chairman need to consider very carefully a dynamic in which a chairman is sitting in judgment over his or her successor. This can introduce a layer of complexity to what is clearly the most important relationship in the business.

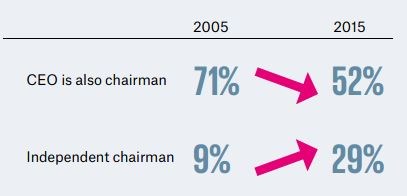

VIEW FROM THE US: S&P 500 COMPANIES

The chairman and CEO roles are still frequently combined in the US. However, a gradual, yet remarkable shift toward separating the functions has taken place over the past 10 years

RISE OF OUTSIDE DIRECTORS: INDEPENDENCE

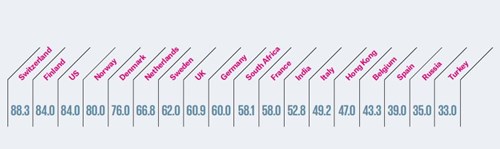

In many countries, board committees are required to have a majority of independent directors, with the audit committee comprising only independents. Boards with two-thirds or more independent directors find it easier to populate an increasing number of committees

Independent directors (%)

For companies to be listed on the world’s exchanges, authorities often demand that a majority of directors are independent. To be classified as independent, directors should be free of conflicts of interest.

However, independence is more than that: it is an attitude. Independent thinking is essential if outside directors are to challenge and support executives properly, and avoid groupthink. The best outside directors identify closely with the business while bringing objectivity to the board’s deliberations. The truly independent director has the interests of all the shareholders at heart and continually asks: what course of action will yield the greatest chance of success for all investors in the long term?

If a director is not prepared to question or, when necessary, challenge the executive on strategic issues, he or she brings little value to the board.

On the other hand, relevant experience among non-executive directors is essential. It is a mistake to rule out potentially useful board members because they do not comply with an overly rigid definition of independence.

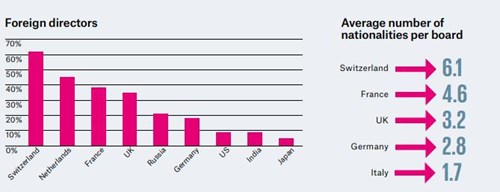

INTERNATIONAL DIVERSITY: NATIONALITY

Swiss boards have not only the highest proportion of foreign directors, but also the highest number of different nationalities. Globalization and a shift in world trade toward the East is likely to result in boards becoming even more internationally diverse

In many countries, non-nationals now account for more than a quarter of board directors, often offering much-needed experience in strategic markets, in addition to technical expertise. But international diversity may not be easy to create or to maintain – especially when the element of long-distance travel is factored in to an already steep commitment. For that reason, the majority of foreign directors for any given company tend to hail from the same continent.

TALENT: RENEWAL

In an era of accelerating change, growing complexity and unprecedented disruption, the fact that today’s boards are older than a decade ago is a source of concern. While boards need experience and maturity, they also need to be continually refreshed. The best boards encourage individual directors to think critically about their own contributions and whether the experience they bring is as relevant today as when they joined the board

Over the past 10 years, boards have gradually been getting older, for a number of reasons. Fewer serving executives have time to commit to an outside directorship; not all countries have term limits for directors; and mandatory retirement ages, where they exist, have steadily been going up.

As boards age, investors often become frustrated. They question whether it is sensible to have the same people on your board year after year in an era when demographics, technology and consumer behavior are constantly changing and business models are getting disrupted. Boards need to step back and think as an activist would, asking themselves whether the diversity of skills around the boardroom table reflects the strategy of the business and its stakeholder universe.

EFFECTIVENESS: ASSESSMENT

How well a board does its job cannot easily be captured in numbers. Statistics don’t tell us how well a board is run, the nature of the debate, how directors are relating to each other, how well they really understand the business or whether they have the confidence of management.

Even so, annual board assessments are becoming more common and they play an increasingly critical role in improving board effectiveness. When done well, assessments can result in improved processes, greater accountability, more transparent communication, enhanced trust and better decision-making.

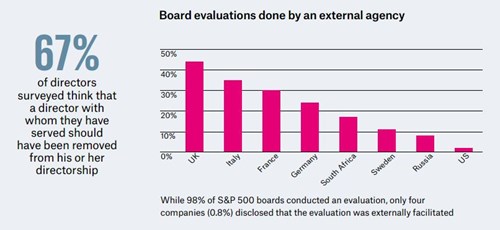

An external assessment conducted by an experienced and neutral facilitator will provide a far richer and more nuanced picture of how the board functions and how effective it is than one that is internally managed and purely questionnaire-based.

Many governance codes often recommend using an external facilitator every three years, although some companies prefer such a review every year. Despite a growing acceptance of the practice, few guidelines exist and the standards of how assessments are conducted vary. This is surprising given how much is at stake for the company – and the potential benefits.

36% of directors surveyed have served on a board that used evaluations to remove a director

Board evaluations done by an external agency

Boards that have a positive view of annual assessments are more likely to improve. Many board directors view external board evaluation negatively, as a process designed to reveal their shortcomings. By embracing constructive criticism, a board can show investors that it is functioning effectively

PAYMENT: DIRECTORS’ FEES

The compensation of outside directors should be in line with experience and the time commitment expected, but it should not be equal to that of top executives, as this could compromise the directors’ independent view of the organization. An outside director whose lifestyle depends on fees from a single organization cannot be regarded as totally independent

Fees paid to non-executive directors vary enormously around the world, with the US and Switzerland compensating their independent board members most generously.

In most countries, directors earn additional fees to chair committees or serve as a committee member, lead director or senior independent director.

Compensation methods for non-executive directors can include any combination of retainers, board and committee meeting fees, share grants, bonuses and other emoluments.

This can make comparisons difficult. In addition, disclosure requirements are thorough in some countries, but patchy at best in others. The chart above shows the wide range of retainer and total compensation available to non-executive board directors in a selection of markets where this information is readily available.

WHO’S NEXT? SUCCESSION PLANNING

Having the best possible talent around the boardroom table really matters. Boards need to be fluid and adaptable, capable of focusing on short- and medium-term issues while safeguarding the future health of the business. Boards with a long-term vision tend to be the ones taking succession planning seriously.

Let’s start with the CEO. A carefully planned and rigorous succession process can last between one and four years. Because most non-executive directors are unlikely to be involved in a process like this more than once or twice in their career, they need to be supported by an experienced adviser who can escort them through the procedure and draw on best practice. For the most part, the mistakes that lead to hasty appointments or to the unnecessary departure of internal candidates can easily be avoided.

Boards achieve the best results when they tackle succession planning well in advance, with the full support of the CEO. Some boards are reluctant to raise the issue mid-way through the CEO’s tenure and thus delay the process, creating unnecessary stress.

The ideal time to discuss the topic of succession is shortly after a new CEO has taken up the post. When succession appears regularly on the board agenda it is understood as an aspect of planning rather than a question mark over the CEO’s competence.

Succession planning is about far more than the CEO, of course – it needs to span the whole board. And it takes time. It is still all too common for boards to address director succession only when facing an impending vacancy. By thinking about the big picture and planning further ahead, boards increase their options and make it easier to secure the very best talent when it is most needed.

Strategic perspective

Some nomination committees maintain a skills matrix in order to fill gaps in directors’ competencies to the benefit of the business. Since the balance of skills changes with each new appointment, this matrix needs to be reviewed continually, identifying opportunities for fresh perspectives that would be most relevant to the organization’s future.

Board composition has to be aligned with strategy. Any new appointment should always be viewed in the broadest possible context, taking into consideration the company’s goals, term limits, and the relevance of each director’s skills and experience, both today and three to five years from now.

This point cannot be made too strongly. When the company’s strategy shifts, tough questions need to be asked about the suitability of the present board to support and monitor management while that new strategy is being executed.

This is particularly true during a period of disruption or when the business is facing a new external challenge that requires some board-level expertise – for example in digital strategy, multichannel operations, cybersecurity, sustainability, regulation or government relations. In such cases, it may make more sense for the board to add an expert in a particular area, rather than confront the challenge with the current team or seek advice from outside consultants.

EDWARD SPEED

Edward Speed is Chairman of Spencer Stuart and active on CEO succession and board searches globally. He has 25 years’ experience in recruiting chairmen, non-executive directors, CEOs and top management for leading public and privately owned companies.

SPENCER STUART

Spencer Stuart is a global executive search and leadership advisory firm. Founded in 1956 and privately owned, it works with clients across a range of industries, from major multi-nationals to emerging companies, to nonprofit organizations.

Data: Spencer Stuart Board Indexes / 2016 Global Board Director Survey: Spencer Stuart, Womencorporateddirectors Foundation, Harvard Business School's Prof Boris Groysberg