Are you ready for CBAM?

Europe’s new CBAM regulation officially entered into force in May 2023. As the EU Executive works to develop the final CBAM methodology, companies should take this unprecedented opportunity to engage with EU policymakers and other stakeholders. The EU’s choice of approach will also influence the mechanisms being developed by other countries and international institutions such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The new rules will add to growing environmental impact reporting requirements on companies, which are giving the public and investors more information than ever before. Without well thought-out narratives and engagement strategies to explain their path to net zero, companies risk damage to their reputation and valuation.

Toward a European carbon tax

The European Union is aiming to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% below 1990 levels by 2030. Its “Fit for 55” package, part of the larger European Green Deal, plans to replace the current system of free carbon credits under the EU emissions trading system (ETS) with a carbon tax over time. The new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is a major step toward changing how Europe addresses the risk of carbon leakage, which occurs when companies move operations to regions with fewer environmental regulations to save costs related to climate policies like the ETS. CBAM will ensure that the carbon price of EU imports is equivalent to the carbon price of domestic production to reduce the risk of leakage and encourage non-EU producers to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

The CBAM introduces a carbon tariff on imports in emission-intensive sectors currently benefiting from free allowances under the ETS, including cement, iron, steel, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity and hydrogen. While the extension to hydrogen was much debated, policymakers designed it to deter the EU from becoming overly reliant on hydrogen imports. Under the CBAM, renewable hydrogen will be considered as having zero emissions, and imports of this type will not incur CBAM charges. In the future, the scope of the CBAM may be extended to other industry sectors such as organic chemicals and polymers.

The levy will affect imports from all countries outside the EU, except Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. Additional countries may be added to the list of exclusions in the future if integrated or linked to the EU ETS or an equivalent mechanism. If an EU importer can demonstrate that it has already paid for the carbon used during production of the imported goods in another country, the number of required CBAM certificates will be reduced accordingly.

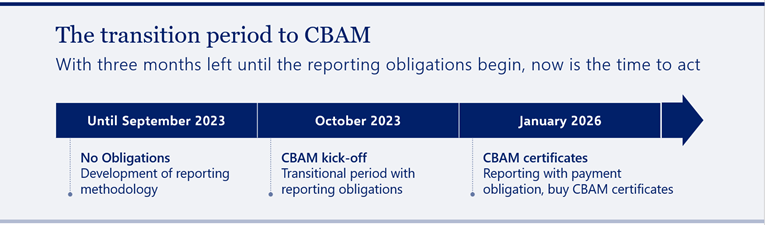

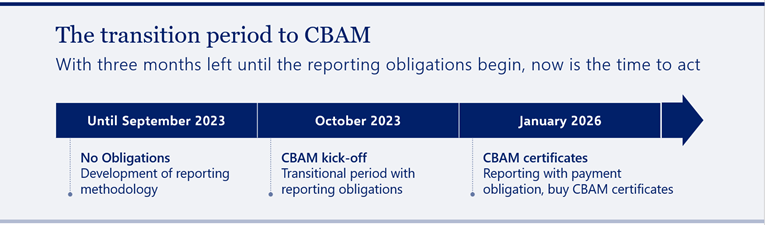

The CBAM will be phased in over time across different industries. It will apply at first from October 1, 2023, with a transitional period until 2025, during which time importers will only be subject to a reporting requirement on direct and indirect emissions for cement, fertilizers and electricity and limited to direct emissions for iron steel, aluminum and hydrogen. Starting in 2025, importers will be able to apply for the status of authorized CBAM declarant.

From January 2026 onward, when the final framework is expected to take effect, only authorized declarants will be able to import CBAM goods into the EU and will be required to submit a yearly CBAM declaration. They can purchase CBAM certificates at any time. If a carbon price has been paid in the country of origin, a reduction can be claimed by declarants.

The CBAM will eventually replace the free emission allowances mechanism under the current EU ETS rules, but with a nine-year phasing-out period. (See Annex.) This phaseout of free allowances serves to strengthen the carbon price signal in line with Europe’s decarbonization goals.

Revenues from the CBAM will contribute to the EU’s budget, including to support climate and energy-related activities.

Impact on companies and international trading partners

The CBAM is likely to have significant implications for companies outside the EU, particularly those with high carbon emissions. Countries with the largest share of CBAM-covered products such as China, Mozambique, Serbia, Turkey and the UK would be the most impacted. To counteract this, traders would need to invest in cleaner technologies and processes or implement their own carbon-pricing mechanisms.

The CBAM will also have an impact on EU industry as EU producers could see their output increase as competing products from third countries fall under the CBAM. However, EU downstream producers that use materials that fall within the scope of the CBAM in their supply chains, such as automotive and construction, could incur higher costs, unless they find less carbon-intensive inputs.

Reporting requirements will tighten, which poses additional challenges for companies and is in line with other recent EU legislation such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which aims to enhance transparency and accountability through its requirement for disclosing scope 3 emissions.

So far, no other jurisdiction has established a carbon levy. In the US, only a limited carbon border adjustment is in place as part of the state of California’s cap-and-trade system for electricity imports. Canada, Japan and the UK are also considering CBAMs. China launched a national ETS in 2021. Around 45 countries have some type of carbon-pricing initiative in place.

The discussion around carbon pricing has opened the debate for the creation of a “climate club” for a wider agreement on a common minimum carbon price.

EU-US: The green trade friction

The CBAM is the latest in a comprehensive set of measures in both the EU and US to advance carbon neutrality by offering incentives and imposing costs on companies.

The European Commission’s Green Deal Industrial Plan includes the Net-Zero Industry Act, which sets targets for clean-tech capacity and streamlines the granting of permits, and the Critical Raw Materials Act, which ensures adequate access to the raw materials needed for this scale-up.

Taken together, CBAM and the Critical Raw Materials Act will have a significant impact on companies. They will, for instance, increase battery costs for EU automotive companies and grid-scale battery manufacturers who will have to rely increasingly on domestic production of critical raw materials.

But the Green Deal also includes access to EU funds and green subsidies, stemming from the new European Sovereignty Fund. The long-awaited reform of the EU electricity markets resulting from the challenges of the energy crisis is expected to lower energy prices and support renewable energy production. But implementation of this legislation is still some way off.

In the United States, the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act includes large green subsidies and tax incentives for US companies that shift production from overseas to the US.

Critics on each side of each side of the Atlantic have accused the other of favoring domestic production at the expense of the global trading system.

Download the full report here.