German companies want to open the door of opportunity for the nation’s refugees.

Millions have fled hardship and war in their home countries for an uncertain future in Germany, one of the most prosperous nations in Europe. Allowing such a tsunami of refugees into the country was in itself a difficult move, but it was only a prelude to the bigger challenge: how can so many poor, unemployed, non-German-speaking people be integrated into the nation’s economy?

The government has been at pains to answer the question, as the issue of accepting refugees has sharply divided public opinion. Many would like to see Germany close its borders to these migrants and their voices are gaining strength. But that pointed debate won’t address the needs of those already in the country. Initially slow to respond to the largest wave of immigration in 2015, German businesses are now actively engaged in bringing this population into the workforce.

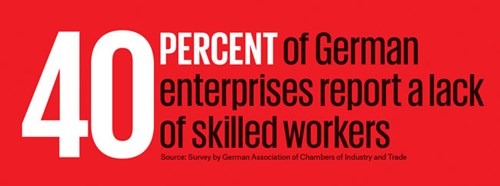

These initiatives stem in part from a practical need to address an increasing shortage of workers. Nearly 40 percent of German enterprises report a lack of skilled workers as a risk to business development, according to a recent survey by the German Association of Chambers of Industry and Trade. A 2014 report from the Cologne Institute for Economic Research found a shortfall of 117,300 skilled workers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. That number is expected to be nearly a million by 2020. Refugees, most of whom are unskilled, can provide a robust general labor force from which talent for skilled positions can be identified and trained.

“For years, we’ve been talking about demographic problems and the fact that skilled workers will be in short supply,” says Barbara Costanzo, Vice President of Group Social Engagement at Deutsche Telekom. “Businesses have the advantage of being able to act faster than political organizations.”

“Every company will have to scramble to find workers,” says Annette Mock, Director of the Refugee Aid Project for global courier Deutsche Post DHL, a Euro Stoxx 50 company. “We have people coming to us now who are urgently seeking employment and are eager to integrate.”

Germany knows all about the challenges of integration. With the fall of the Berlin Wall,

9 million East German employees were waiting to be integrated into the Federal Republic. But even with a common language, the different Cold War cultures of East and West made the effort difficult. From 1989 until 1991, as businesses were restructured, more than 2.1 million people lost their jobs. Many older East Germans remained unemployed.

Significant cultural differences also exist with today’s refugees; language barriers make integration even harder. Over a million refugees came to Germany in 2015 from countries such as Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Albania and Kosovo. That number was cut by more than half in 2016, but remained in the hundreds of thousands. Some feel the newcomers need to learn German before they get a job; others are convinced they can do both at once.

“Someone who wants to become, say, a tiler, won’t need the pluperfect tense in German,” Sebastian Muschter, a former director of the Berlin refugee center LaGeSo and former McKinsey consultant, told Die Welt recently. “But he will need job-related vocabulary fairly quickly.”

With or without language barriers, employers engaging with refugees are often faced with a pool of relatively untrained applicants that is larger than they can handle. Deutsche Post offered 1,000 internships to immigrants but were able to identify and hire “just short of 370 interns” and 14 apprentices, according to Mock. The positions have the benefit of introducing the new workers to skills they may be able to use elsewhere in the labor market, even if they don’t stay at Deutsche Post. The company admits its success has so far been modest. “What we’ve achieved has been a very good step,” Mock says, “but starting with 1,000 vacancies was perhaps a bit optimistic.”

Chambers of commerce are offering seminars and training programs to both companies and migrants, intended to complement those led by federal, state and municipal governments. While a diversity of approaches and a lack of standardization with these programs can present problems, the business community is attempting to coordinate the effort, setting up a network of companies – 1,200 at latest count – that wish to employ migrants.

A separate nationwide initiative, Wir Zusammen (“We Together”), was founded in 2016 and quickly grew to include 150 companies. The group shares resources between businesses, and claims to have placed 2,800 migrants into internships, 630 into trainee positions and 557 into full-time jobs, according to the Financial Times.

Wir Zusammen was the brainchild of Ralph Dommermuth, the billionaire founder and CEO of the country’s largest internet provider, United Internet. “I don’t believe that we cannot integrate them,” Dommermuth told the Financial Times recently. “If we as a society want it, we can do it.”

In tackling aspects of the labor problem, some corporate foundations are also aiding immigrants. The Airbus Foundation, for instance, has no programs for refugees but encounters the population in its work with underprivileged youth.

“In the Airbus Foundation’s Flying Challenge Program, for example, Airbus employees mentor disadvantaged young people for six to 12 months and assist them in career training,” says Federica Cantatori, who is responsible for the training programs. “Many of the young people in the Flying Challenge have an immigrant background.”

These efforts pay off socially and economically. “We know from studies that companies that systematically implement a sustainability strategy and, in particular, take on corporate responsibility, are more crisis resistant and more profitable,” says Birgit Klesper, Senior Vice President Group Corporate Responsibility at Deutsche Telekom.

Public budgets also benefit. According to a recent report from Berlin’s German Institute for Economic Research, additional investments of €3.3 billion ($3.5 billion) in the language skills and education of refugees immigrating in 2015 can reduce fiscal costs by €11 billion by the year 2030.

The same study also finds that job training increases refugees’ chances for finding steady work by around 20 percentage points and gives them a greater shot at a higher wage.

Despite all the positive activity, few have any illusions about the challenges surrounding such a large influx of refugees. Raimund Becker, a member of the executive board of the Federal Employment Agency, says the rate of integration should match that of migrants historically.

“We expect that between eight and 10 percent will find jobs in the first year, and around half will have a job by the fifth year,” Becker said. Around 70 percent should be employed in 15 years, he added.

Meanwhile, Germany’s refugee crisis is being echoed around the world. The US in particular has been roiled by President Donald Trump’s effort to halt immigration from some Muslim countries, including Syrian asylum seekers. As in Germany, some US-based companies are pledging to step up their hiring of refugees and immigrants. Worldwide, it is clear that this mass movement of people across borders will remain a growing business concern.

Katrin Meyer-Schönherr is a Partner in Brunswick’s Munich office and Head of the firm’s Insight practice in Germany. Carl Graf Von Hohenthal is a Partner and Senior Adviser in the Berlin office.

Illustration: David Plunkert