Prolonged trial of strength between US and China.

The current trade war between the US and China is giving considerable stress to businesses in the line of fire. Even after the US mid-term elections, the tension will not go away. Anti-China emotions are growing in the US. Peter Navarro described ‘death by China’. Steve Bannon advocates ‘economic warfare with China’.

Manufacturers in China, both Chinese and non-Chinese, are reacting. Distribution centers for consumer products are shifting back to HK from China. Mainland electronic companies are relocating facilities to Taiwan so that final products exported to the US are not from China and therefore, subject to rules of origin, not liable to new US tariffs.

As US Customs tightens compliance with rules of origin, trade diversion from China to Southeast Asia and other countries will be followed by investment diversion. China will instead supply components to countries exporting to the US. The trade war is accelerating a process already underway, which is the relocation of lower value-added manufacturing activities from China to Southeast and South Asia, and increasingly also to Africa.

We can expect China to give greater emphasis to the Belt and Road Initiative as it girds itself for a prolonged trial of strength with the US. Chinese leaders do not want a fight with the US and are prepared to meet US demands more than halfway, but they cannot afford to be humiliated in the eyes of their own people. For decades to come, China’s growing economic, political and military weight is bound to create episodic instability in relations with the US, Europe, Russia, India and Japan.

ASEAN as beneficiary

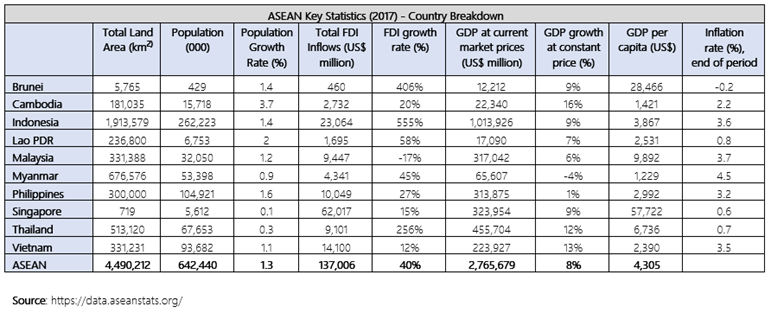

As the world adjusts to shifting geopolitical weights, the greatest beneficiary is ASEAN. ASEAN is non-threatening to the major powers. The variable geometry in ASEAN’s construction enables it to adjust to regional stresses and strains by sometimes tilting in one direction, sometimes in the other. The current trade war between the US has made ASEAN an attractive alternative or supplementary manufacturing base to China.

ASEAN is perfectly positioned. China’s growing importance as an importer is a gradual sea change which is still not yet widely noticed. It will not be many years before China becomes the biggest market in the world, not only for raw material and food, but also for manufactured products and services. This has profound consequences for global trade, economics and politics. In November this year, Shanghai will host the first annual China International Import Expo. It will be on a massive scale and a signal to the world. ASEAN, which has a free trade agreement with China, will becoming a major manufacturing base for export not only to advanced economies but also to China.

The integration of China’s and ASEAN’s economy is well underway. When President Xi announced the Belt and Road Initiative in Jakarta in October 2013, he expressed the hope that China’s bilateral trade with ASEAN will reach one trillion dollars by 2020. For this target to be achieved, physical connectivity has to be improved, hence the importance of Belt and Road projects. Border procedures have to be further simplified. China-ASEAN logistics are improving year by year, enabling a more complex division of labor. The 10 countries of ASEAN see the benefits and vie with one another for Chinese trade and investment.

Vietnam

Vietnam has become China’s most important trading partner in ASEAN. This may come as a surprise to those who only read about the quarrel between the two countries over competing claims in the South China Sea. The Friendship Pass between Vietnam and China, once bitterly fought over, is now worthy of its name. Vietnam’s costs are much lower than China’s; its workers no less hardworking or intelligent. It is also skillfully exploiting its geopolitical position as a counterweight to China in the eyes of competing powers. Pre-Trump US encouraged Vietnam to join TPP for precisely this reason. Institutionally, Vietnam hews close to the Chinese model. Like China, it is moving determinedly against rampant corruption. Despite similarities to China, however, Vietnam defines its own identity in contradistinction to China. Unlike the Chinese Communist Party which has split many times in its history, the Vietnamese Communist Party, with as long a history, has never split. Vietnam is set to become an economic powerhouse in ASEAN.

Thailand

On the surface, Thailand’s political instability will persist. General elections in February next year will not restore the country to full democracy because the Army’s role remains dominant. Many Thais think this a good thing. A new king is asserting a new position which will take time to clarify. Beneath the surface, however, Thai society is remarkably stable. Thailand’s economic prospects are bright. It benefits from China’s rise without having a common border with China to complicate bilateral relations. A high-speed rail connecting Bangkok, Vientiane and Kunming is being built and planned to be completed in 2021. Thailand also maintains good relations with the US with which it still has a security alliance. Japanese companies feel the most comfortable in Thailand. Thailand’s geographical location gives it a natural centrality in mainland Southeast Asia.

Laos

The Mekong, once a river dividing two worlds, now connects China to Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. Between Vietnam and Thailand are Laos and Cambodia. Laos, which saw more bombs fall on it than on all of Europe during the Second World War, is making steady economic progress. Many bridges across the Mekong link it to Thailand. China is building the fast rail from Yunnan to Vientiane at great speed. Laos, which is the origin of 60% of Mekong water flowing into the South China Sea, has abundant hydropower potential and is becoming a major exporter of electricity to its neighbors. From landlocked, it is now land-linked.

Cambodia

The recent general elections in Cambodia were heavily loaded in favor of the incumbent. Notwithstanding, the voter turnout was high, and many Cambodians were relieved that there is political stability. From Year Zero not long ago, when much of the country’s elite was killed in a genocide, the country has made remarkable progress. The physical infrastructure is improving year by year. An economy that was mainly dependent on rice exports, apparel manufacturing and tourism is graduating to higher value-added manufacturing. China is an important source of investment but by no means the only one. In the last few months, manufacturers seeking an alternative to China are showing sudden interest in Cambodia.

Myanmar

Myanmar has received much negative news in recent years over the plight of Muslims in Rakhine state but that is far from being the whole story. The humanitarian crisis demands urgent attention. Many outside Myanmar call them Rohingyas, including Pope Francis, but the name ‘Rohingya’ is pointedly not used by the Myanmar Government and Army because it was not an ethnic group identified among the 135 listed in the Constitution of the Union of Burma. That Constitution was drawn up in 1947 under the leadership of Aung San (father of Aung San Suu Kyi) who founded the Burmese Army and led the struggle for independence. The complicated history of the Rohingya problem has deep historical roots going back to the British Raj in India (which included Burma) and, before that, to the kingdom of Arakan. It is important to separate the humanitarian issue, which cries out for urgent international attention, from the political issue of indigenous citizenship, which is principally a bilateral problem between Myanmar and Bangladesh. There is also the challenge of terrorism. In a recent lecture in Singapore, Aung San Suu Kyi reminded the audience that ‘the danger of terrorist activities, which was the initial cause of events leading to the humanitarian crisis in Rakhine, remains real and present today’.

However, despite the Rohingya problem, the Myanmar economy is gradually picking up speed. Because of her reluctance to use many capable senior officials from the previous military government, Aung San Suu Kyi’s government lacks expertise and experience. Domestic and foreign investors are frustrated by the slow speed of decision-making. The physical infrastructure is still woeful. China’s Belt and Road Initiative is therefore a godsend. In September 2018, an MOU to establish a China-Myanmar Economic Corridor was signed. Across the river from Yangon, a Chinese SOE (subject to a Swiss challenge on terms and conditions) will help to build a new city, like a Pudong to Shanghai, with the immediate objective of creating two million manufacturing jobs in five years. If Myanmar can quickly improve the efficiency of public administration, it stands to benefit hugely from investment diversion caused by the trade war between China and the US. China is already Myanmar’s number one investment partner.

Indonesia

Indonesia, under President Jokowi, has made great strides in the last 4 years. Hundreds of infrastructural projects are being implemented across this vast archipelago. Jakarta, if not Java as a whole, has become a giant construction site. With better physical connectivity, logistics costs, which are presently high, will come down. Indonesia enjoys competitive advantage in resource-based industries because of abundant natural resources. Higher-value manufacturing investments are, however, not as forthcoming. Tightly-organized modern supply chains are intolerant of disruptions especially those caused by natural disasters which seem to affect Indonesia disproportionately. Currently, many investors are a little jumpy because of uncertainty over the outcome of Parliamentary and Presidential elections next year. Longer term, however, with a young and expanding population, Indonesia is on track to become one of the world’s biggest economies after the US, China and India. It is a market which no MNC can ignore.

Philippines

The Philippines is another country in ASEAN which is prone to natural disasters. Every time a super typhoon hits, severe disruption to life and supply chain takes place. This handicaps the ability of the Philippines to attract sophisticated manufacturing. Notwithstanding, the Philippine economy has been growing smartly. Its greatest resource is its people. However, it is a sad commentary on the overall system that many Filipinos are more valuable working outside the Philippines than in it. That the total number of Filipinos working in foreign countries has crested at 10 million is therefore a good sign. As infrastructure improves year by year, partly with Chinese help, the Philippines is becoming more attractive to manufacturing investments for fast-moving consumer goods, especially by American companies. President Duterte is an atypical leader who, despite being shunned by the Manila establishment, has done reasonably well for the economy and remains wildly popular among large segments of the population inside and outside the country. Whoever his successor may be in 2022 is unlikely to take on his firebrand style and may re-triangulate the country’s foreign policy vis-a-vis China and the US. Once the Philippine economy reaches a certain level of development, the global Philippine network that the country can tap gives it a unique advantage in ASEAN.

Malaysia

Malaysia had an unbelievable stroke of good luck when the egregiously corrupt administration of PM Najib was peacefully replaced in the general elections of May 2018. In the euphoria which followed, expectations rose to the sky. That has since subsided some. But there is no doubt that a new, happier chapter has opened in the history of Malaysia. The redoubtable Mahathir, still sprightly at 93, appointed a Chinese as Finance Minister and an Indian as Attorney-General. There is a chance that a brain-drain which went on for decades may now be reversed. Malaysia is a well-endowed country with good infrastructure and a relatively well-educated population. Higher oil prices will make it easier for the new government to mend its finances. Boondoggle Belt and Road projects are rightly being renegotiated (to China’s embarrassment). But Malaysia’s close links with China will not be too badly affected, neither under Mahathir nor under a future PM Anwar. Malaysia sees itself as the successor state to the old Malacca which flourished on an earlier China trade under the protection of Ming China.

Brunei

Tucked between Malaysia and Indonesia, tiny Brunei floats along nicely, buoyed up by rising energy prices and a rising Asian tide. ASEAN provides an inner zone of stability and security. Strengthening relations with China provide the sultanate with additional insurance. Brunei’s EEZ in the South China Sea has abundant oil and gas reserves. China has never objected to Brunei’s EEZ claim which cuts deep into China’s nine-dash line.

Singapore

Singapore’s nonpareil geographical and cultural position in maritime Asia is not an accident of history. 199 years ago, Singapore was established by the British East India Company for the 19th century China trade. The 21st century China trade is much bigger and will take Singapore far. Singapore is a classic hub for goods, services, information, intellectual property and money. A pioneer leader of Singapore once remarked that Singapore should always welcome badly-treated people and badly-treated money. At its core, Singapore is a hub for people and cultures from different parts of the world. All of ASEAN, indeed much of the world, has its reflection in Singapore. Not surprisingly, Singapore is a strong proponent of free trade. When trade is not so free, Singapore helps to iron out distortions. Even if there is a breakdown of the WTO, Singapore’s economic role in international trade and finance will not diminish. It may even be enhanced. Never taking a tranquil regional or international environment for granted, the Singapore government has long taken the precaution of negotiating a slew of free trade agreements, including bilateral ones with the US, Japan, Korea, China, Australia, India, the GCC and Europe, and regional ones like ASEAN and CPTPP (TPP without the US). In ASEAN’s variable geometry, Singapore is a pivot point. Singapore’s biggest challenge today is domestic. A sizable segment of the population is reacting against rapid globalization and growing income inequality. Since the general elections of 2011, the people and government have turned inwards. But it is necessary for Singapore to re-establish its internal balance first before reopening itself to the many opportunities surrounding the city-state.

ASEAN neutrality

The integration of China’s and ASEAN’s economy is being quickened by trade and political tensions between China and the US. For every ASEAN country, China is already the largest trading partner. However, China knows that, whatever the degree of integration, ASEAN will not allow itself to be locked into China’s embrace. In 2002, when the framework agreement for the ASEAN-China FTA was signed in Phnom Penh, Premier Zhu Rongji assured ASEAN leaders that China did not seek for itself an exclusive position in Southeast Asia. In addition to FTAs with many countries, including China and India, ASEAN has been a strong advocate of a larger FTA involving China, Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and India, called RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership), negotiations for which may be concluded soon. RCEP encompasses half the world’s people. The more advanced ASEAN countries are also members of CPTPP.

As a neutral regional organization friendly to all the major powers, ASEAN welcomes investments from all directions. The greater the dependence on China, the greater the wish for ASEAN countries to diversify away from China. Japan, the US, India and Europe compete - healthily - for ASEAN’s favor. Japan and India are also involved in building ASEAN’s physical infrastructure. A strong US presence is particularly welcome. To a point, the US military presence helps to maintain strategic balance in Southeast Asia. But if confrontation between the US and China becomes severe, as threatens to be, it is better for ASEAN not to take sides. Understanding this dynamic, China redoubled efforts to work with ASEAN on a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea. There is reasonable hope that the agreement will be signed before too long.

George Yeo is a Senior Adviser at Brunswick Group and Principal in its Geopolitical offer, based from our Hong Kong and Singapore offices. George served in the Singapore Government, as Minister of State for Finance, then as Minister for Information and the Arts, Health, Trade and Industry, and Foreign Affairs (1988 to 2011). These notes are his personal views.