Readers’ Picks

The Dinosaur Strategy

A communications expert targets an audience of 2nd graders. By Mara Riemer.

Running Towards Danger

After moving to Dallas to take charge of Frontier Communications, Nick Jeffery helped orchestrate his greatest turnaround yet. By Elizabeth Volpe and Cleo Levy.

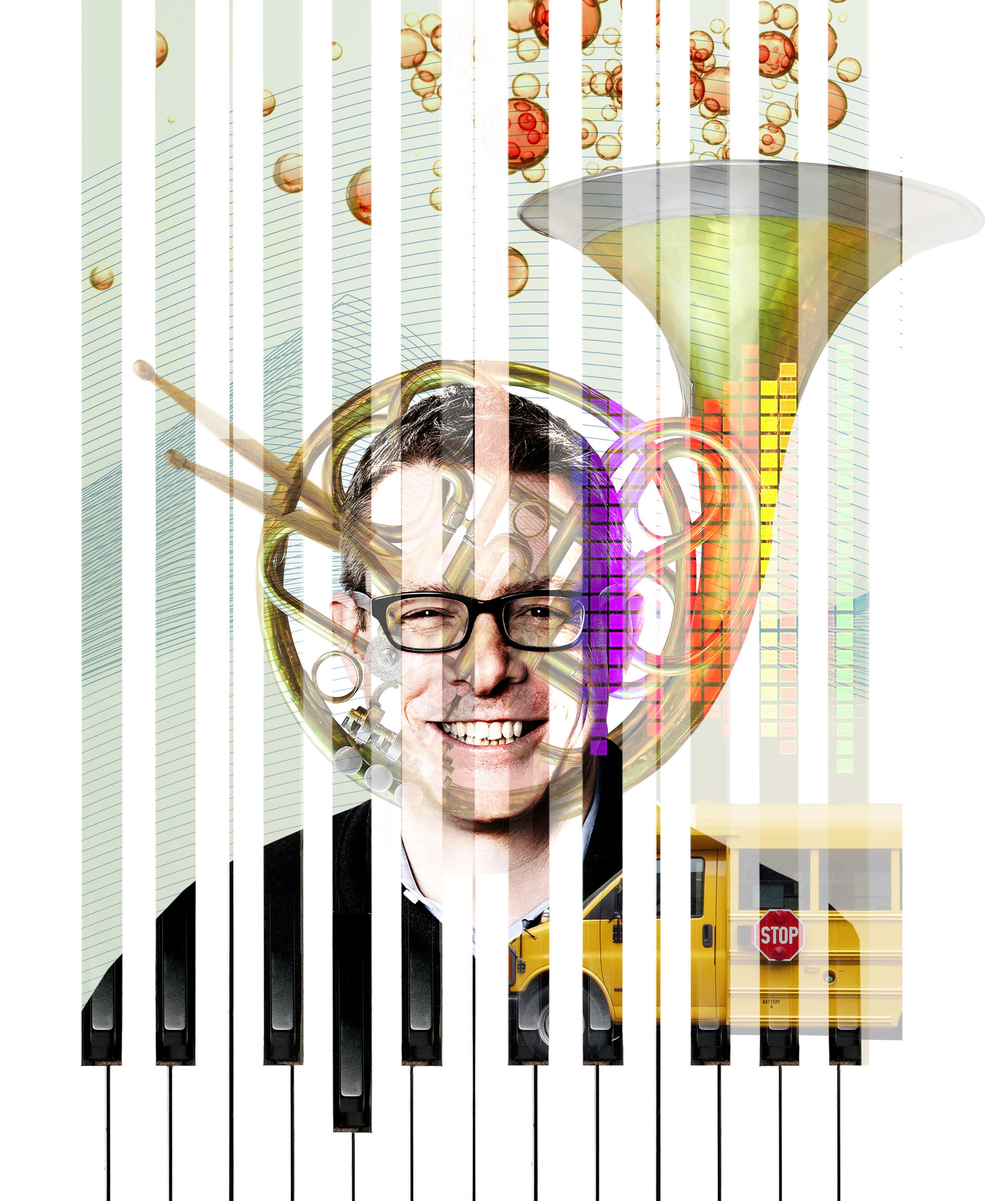

Save The Music

Executive Director Henry Donahue describes the strategy behind the now-independent music education foundation and the importance of strengthening “the base of the pyramid” in local communities. By Carlton Wilkinson