It looks like the page you were trying to reach is no longer here. Many of our older pages and articles have been updated, moved to LinkedIn, or archived to keep our content current and relevant.

Readers' Picks

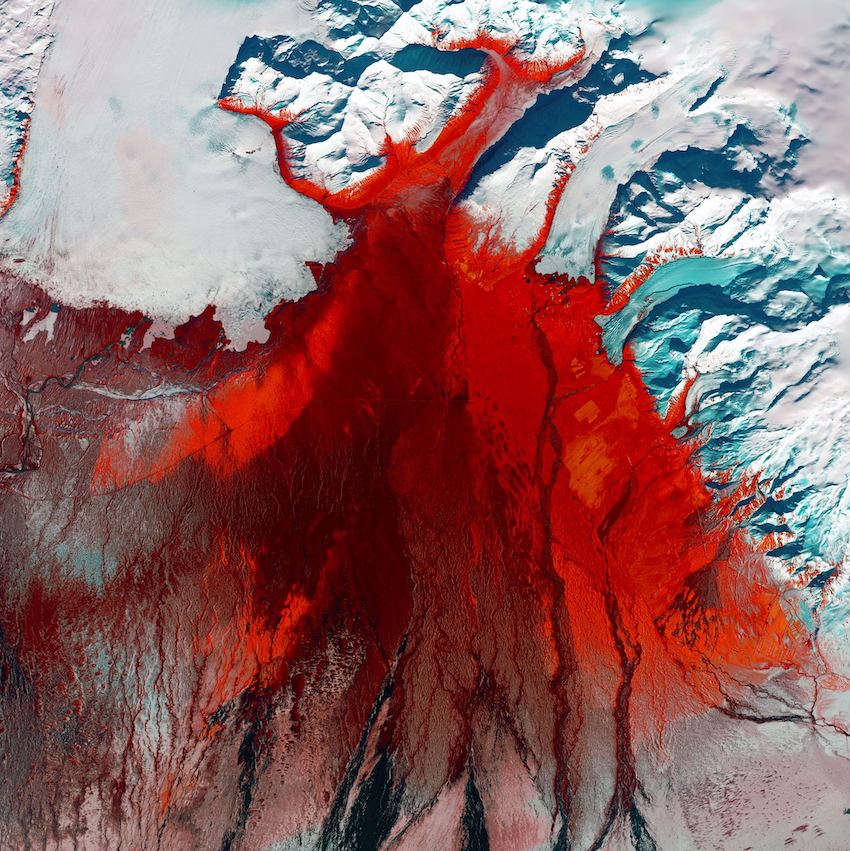

The Natural Resource Chasers

Minerals to fuel the energy transition are the targets in a global race. Xcalibur Smart Mapping CEO Andrés Blanco describes the latest tools and commitments to unlock the value chain.

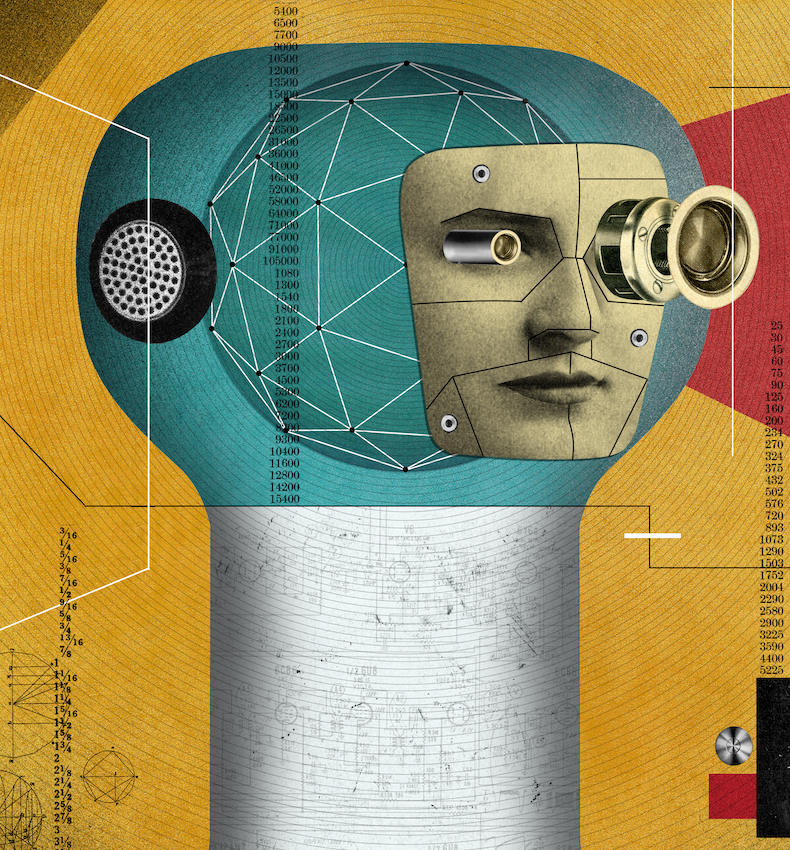

Coming Soon: AGI?

Brunswick’s Chelsea Magnant on how to prepare for the next generation of AI innovation.

Clarity on Climate

Dr. Michal Nachmany is the founder of the nonprofit Climate Policy Radar, a global AI-and-human driven database and open-source platform. She talks with Brunswick’s Carlton Wilkinson about building better decision-making tools for political and business leaders.