BUSINESS LEADERSHIP ON CLIMATE

In this leadership vacuum, ambitious action on climate change is being powered by business. A study of 1,000 business leaders across 99 countries by the United Nations Global Compact and Accenture found that 90 percent of CEOs said they were today “personally” driving their companies’ climate and sustainability agenda.

What is also emerging is a clear model of what that corporate leadership on climate change looks like. We believe it has three dimensions:

1. Business Transformation

Getting to net-zero carbon has become the new North Star for the climate agenda. At the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit, more than 100 cities and 77 countries pledged to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. A group of some of the world’s largest businesses led the way: 87 companies, with a combined market capitalization of $2.3 trillion, committed to set science-based targets that align their business and value chain with limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 (more than 177 companies have made that pledge to date).

A business’s value chain is on average five-and-a-half times larger than the business itself, incorporating how a company’s products are sourced, made, moved and used. To achieve these targets companies are powering their operations with 100 percent renewable energy, pioneering breakthrough technologies, adopting circular manufacturing processes and reorienting their portfolios around lower-carbon products.

The pledges also reflect another key shift: companies setting their targets based on science, not regulation or voluntary commitments. A science-based target changes the question from “Are you doing something?” to “Are you doing enough?” Tied to a 2°C goal, it requires companies to work backward, considering both the role the sector plays in meeting that target as well as their business within the sector.

Research by BloombergNEF found that, even four years ago, 81 percent of S&P 500 companies had set emissions targets, but few were science-based. As of November 2019, more than 680 businesses had publicly shared science-based targets. This included leading companies in the world’s largest-emitting sectors: Maersk, the world’s largest shipping company; BHP, the world’s largest in mining; Heidelberg, the world’s second largest cement company, and ArcelorMittal, the world’s largest steel producer. This level of ambition was unthinkable at the start of the year.

2. System Change

Leading companies look to drive action beyond their operational footprint. That means working with partners like NGOs, government bodies, private-sector peers, and academic institutions, to unlock change in the wider systems they’re part of.

We Mean Business, a nonprofit coalition working with the world’s most influential businesses, aims to accelerate business action across four systems critical to delivering a net zero economy: power, transport, land use and the built environment. And the coalition might just have the breadth to make a difference: We Mean Business counts more than 1,000 companies, accounting for 25 percent of global GDP, as well as nearly 75 nonprofit organizations as partners.

Take transportation, which accounts for nearly a quarter of CO2 emissions worldwide. The Climate Group, a founding partner of We Mean Business, has helped create EV 100, a coalition of more than 50 major multinationals—including DHL, UPS and IKEA—that uses its combined investment power to stimulate mass demand for electric vehicles, invest in the necessary charging infrastructure, and advocate for supportive policies that can boost EV uptake. It’s an area where businesses can lead, as they account for half of all light vehicle purchases (essentially, all vehicles except heavy trucks).

We Mean Business’s hope is that this kind of system-level approach, applied across other heavy-emitting sectors, may unlock effective business action at scale.

3. Policy Advocacy

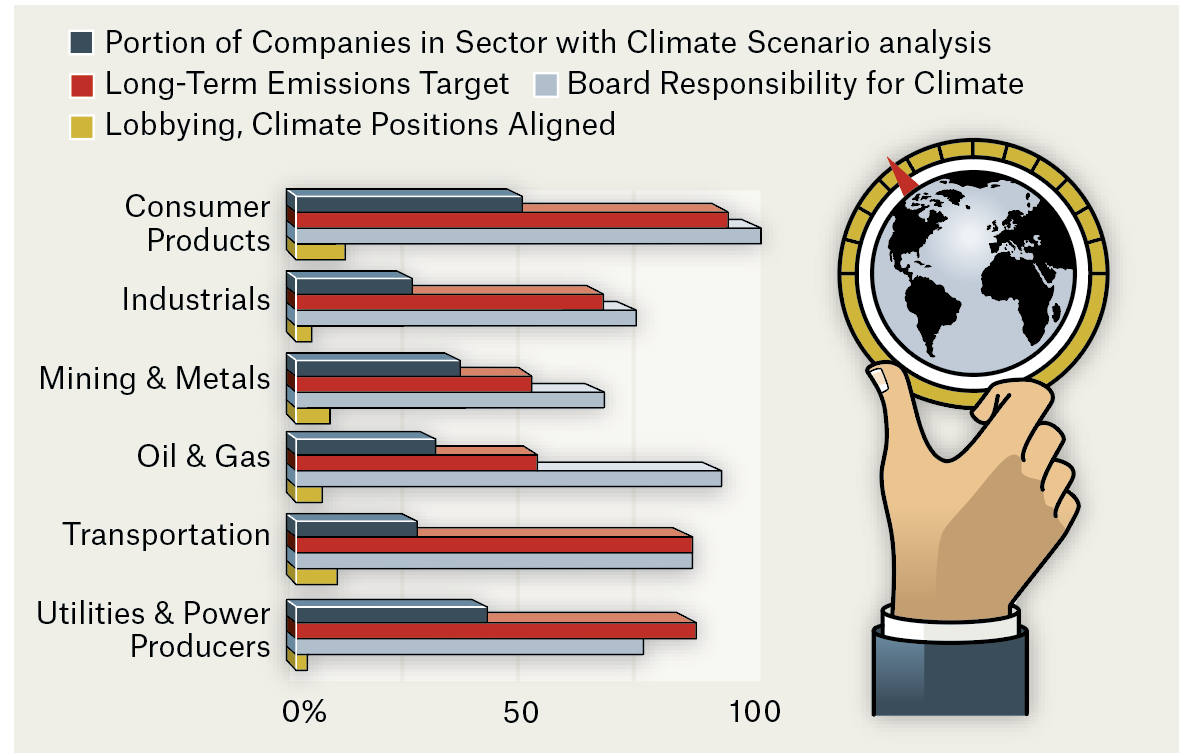

As well as aligning their businesses to net-zero emissions and working to create systems change, businesses also have a role in creating an enabling policy environment for action on climate. Research from Climate Action 100+ suggests this isn’t happening yet: Although companies in most sectors are starting to set emissions targets, far fewer are aligning their lobbying activities (see chart below).

The idea of meaningful advocacy on climate coming from business may evoke a cynical response. “Winds of change or unchanged windiness?” the FT asked after a flurry of bold pledges from companies and countries at the 2019 UN General Assembly. Such skepticism stems partly from companies having pledged support for a range of social issues in the past, yet continued lobbying—or remaining members of trade associations that lobby—for policies at odds with those public pronouncements.

Climate-focused investors and activists are calling out this dissonance when they see it. They’re increasingly impatient with companies that they believe use their voice only to claim public credit rather than inform public policy. Eleven leading environmental and sustainable business organizations published an open letter in The New York Times in October 2019 urging CEOs to sincerely engage on climate policy, while 200 institutional investors, with a combined $6.5 trillion in assets under management, recently called on publicly traded corporations to align their climate lobbying with the goals of the Paris Agreement. The New York Times letter called for businesses to take three specific steps:

1. Advocate for policies at the national, subnational and/or sectoral level that are consistent with achieving net-zero emissions by 2050;

2. Align their trade associations’ climate policy advocacy to be consistent with the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050; and

3. Allocate advocacy spending to advance climate policies, not obstruct them.

Some businesses are heeding the call. The following day, the Sustainable Food Policy Alliance—which includes food and consumer products giants Nestle, Unilever, Mars and Danone—ran the same letter in Roll Call, a US news organization, with the message “we agree.