Given the essential need for systems change, what can any individual company do?

The very first thing is the recognition that the circular economy approach is not about incrementally reducing the harm of a linear product. This is not the typical understanding of sustainability: How do we lightweight something or reduce the negative impacts? This is re-thinking the way to deliver products or services. It requires a shift in business models.

As a company, that means the first thing is to think about what need are you meeting? How could you do that in a different way that aligns to the principles of the circular economy, keeping those products or materials in use and in the system longer?

Are there big companies that are doing this well?

At Philips, for example, they shifted their thinking from selling lightbulbs for business-to-business applications and they’re now selling light as a service. You can buy 400 lumens of light at desk height on a subscription service. They own the lightbulbs that now last ages and the fittings, and you pay for the energy. It’s become a new company call Signify and they’re incentivized in an entirely different way.

Another is Caterpillar, which manufactures heavy equipment for mining industries. They now design the engines or entire truck to be efficiently upgradable and re-manufacturable. By design, it’s become a piece of equipment that can stay in use for very long periods and they’ve built an information system to predict when it needs to be repaired.

Danone supports large scale, regenerative agricultural practices, which build soil health and increase biodiversity, and has pioneered the use of financial instruments to help farmers adopt such techniques. It is also using food design and innovation along the value chain to develop products that are not only healthy but also circular.

And what about small companies, can they play a role?

Certainly: The circular economy works equally for any type or scale of organization, companies large and small. In fact, small companies are becoming disruptors of the “disposability” approach: for example, offering digital subscription services for soaps or cleaning products, where you get one container and subscribe to refillable concentrates. There are fashion startups creating better-designed clothing or re-purposing older clothing. The RealReal is creating secondary markets for luxury goods and has now become a $2 billion startup in just eight years.

With so many companies signing on to the idea, how do you hold them to account to act on it?

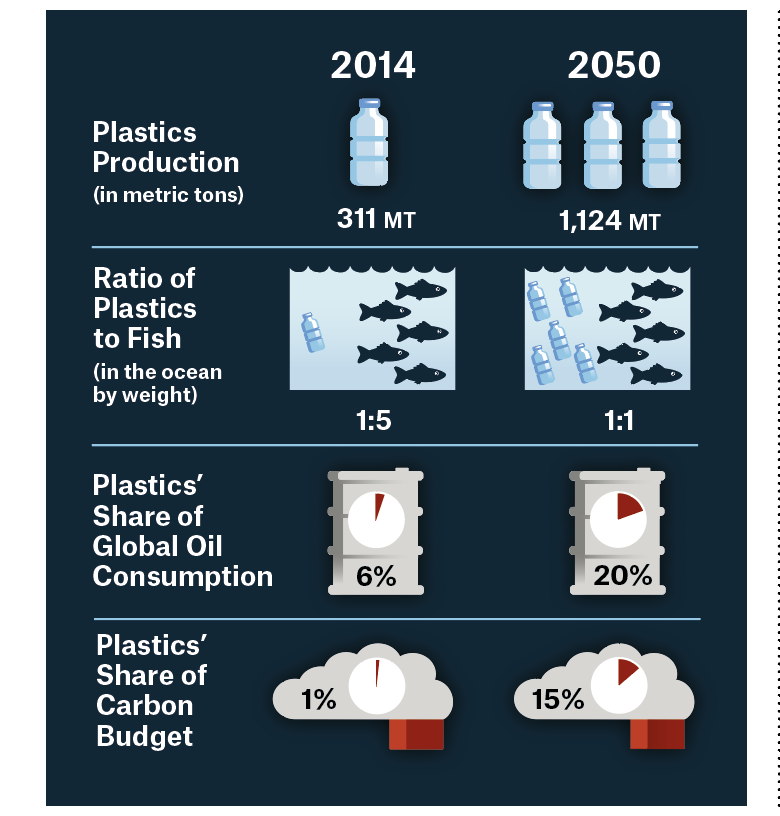

You’re right. That is why we are building data underneath companies that partner with us. We recently released the first report that underpins the Global Commitment where companies declare the amount of plastic they put on the market and the amount of recycled content in their plastics packaging. They have made a commitment that by 2025 100 percent will be recyclable, compostable or reusable against a standard set of definitions that we have built into this commitment. We can track that over time: it’s open and public. Companies want to show they recognise they’re part of the problem and can also be part of the solution. This issue of transparency is only going to get more attention. People will reward the companies that can prove they help.