Let’s talk about integrators. The integrator in a hotel is the receptionist because the receptionist deals with customers, back office, housekeeping, room service, maintenance. In the past, hotel receptionists had no power. Back office functions would not collaborate. When housekeeping saw there was a problem when they were cleaning the room, the bulb is not working, there is water dripping in the bathroom, they would not call maintenance. Because this would have been at the expense of their productivity. So who would discover the problem then? Customers at night.

And whom do they call? Not maintenance. Look for the maintenance phone number in the hotel directory: it’s not there. So they call the receptionist and the poor receptionist would come to kick the heater to make it work or perhaps suggest to the customer, “Let me take you to another room.” So these receptionists were keeping rooms empty on purpose to serve unhappy customers. Or they were giving rebates. All this was at the expense of occupancy rate and average price point.

Then a travel and tourism leader decided to reinforce receptionists as integrators, giving them the power and interest to make all these functions cooperate in the interest of the guests. By doing that, this company increased its gross margin by 20 percent in 18 months. They almost tripled their share price in 18 months.

As you grow, who will be your integrators? At BCG, the integrators are the project leaders. They deal with our clients. They deal with our teams, with our partners, with our expertise centers. And these people have power and interest to make important trade-offs between innovativeness of approaches, practicality of approaches, productivity of the teams, growing the teams, developing the teams.

At home, when I don’t cooperate with my wife, we need two TVs. When we cooperate we need only one. Where are second TVs creeping into your company?

Let’s talk about a railway. European. Highly unionized. State owned. Civil servants. Bureaucrats.

They have to become more customer-centric, improve the quality of their services because of cross-border competition and also competition from low cost airlines, from Uber. Twenty percent of their trains were late. Customers were not happy. Employees were less proud of themselves.

Whenever a train was late, the railway would go through a scientific investigation to know who is guilty for the delay. In which station did the delay start? Which of the key units is the root cause? Was it maintenance? Who was the maintenance manager on duty at that time?

And then the senior leaders call the poor manager and the nightmare starts for that guy. “You have delayed a train. Forget your promotion.” They would spend hours in these scientific investigations because nobody would say, “It’s me who delayed the train.” People would hide. “It’s not me. I wasn’t there.”

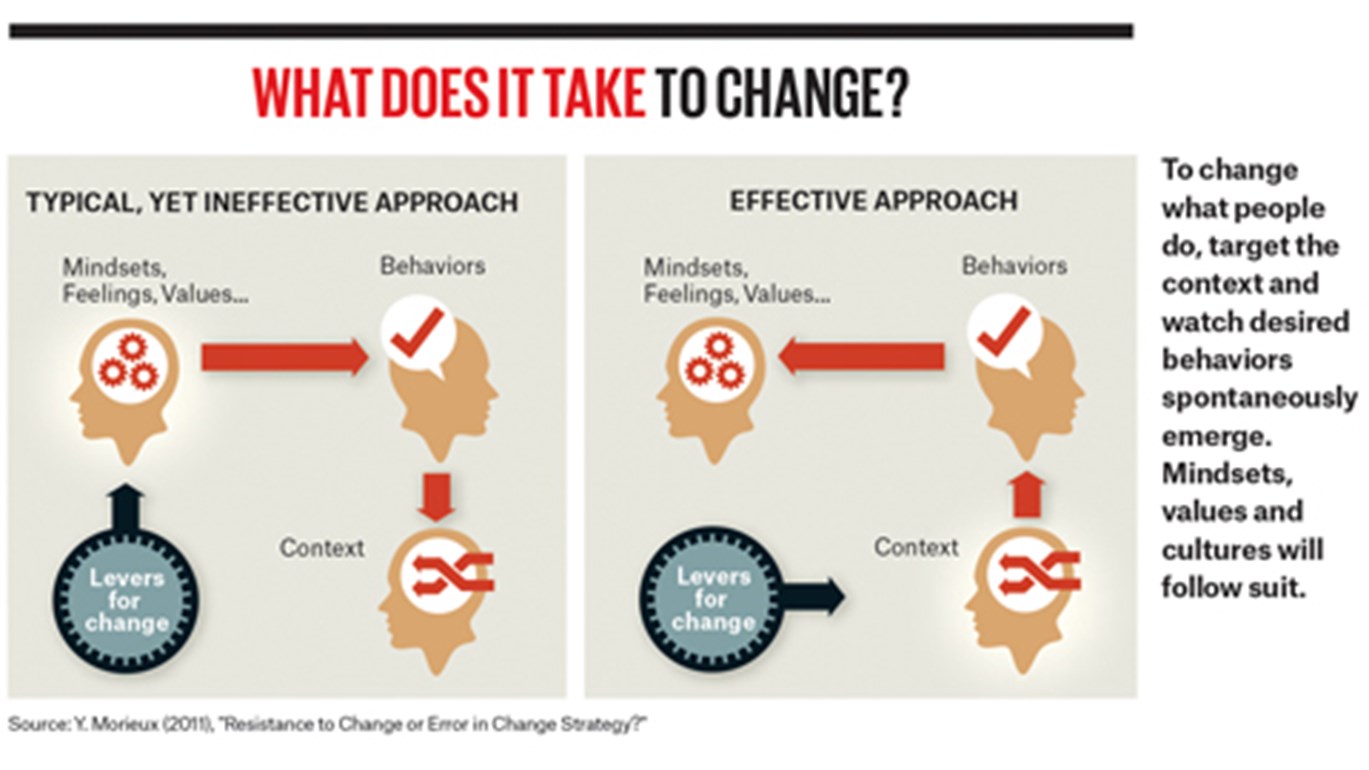

I can tell you that 100 percent of what people do is driven by the context in which they work. If people do what they do, it is because in their context, it achieves their goals; otherwise people would do something else.

At the railway, we discovered that the real goal of these people was to never be found guilty of a delay. Because if they are found guilty of a delay, they are in a nightmare when a senior leader directly calls them.

Still, there are many unexpected events that can happen in a station and during the ride. To aim for perfect punctuality of each unit is unrealistic. So what is the solution? Is it more sophisticated scheduling systems, more employees in each unit, more time, more trains, (i.e. more resources)?

How about more cooperation? Indeed, with cooperation it would be possible to make sure that a delay in some operations would not translate into late arrivals for trains.

For instance, if a train in maintenance is delayed five minutes, maintenance could tell the station. Then the station people could position passengers or make the train arrive in a faster track. Eventually the boarding of passengers in the station would not take as long and the initial 5-minute delay would be eliminated. Of course, this kind of cooperation was not typically happening because each unit was focusing on its own operations to avoid being found guilty of a delay.

When the senior leaders of the company saw the analysis, they realized that the root cause of delays was the rule that focused on determining who to blame for them. After all, people usually don’t decide to be the root cause for a delay. But when units don’t cooperate to help others, they have decided not to cooperate.

So the senior leaders came up with a new rule: when one unit delays the other units, these will take the blame, as long as the root cause unit was transparent and told the others about its own delay. If after some time the same people are still creating the same root cause problems because they have not done their continuous improvement homework, then they will take the blame. The overall criterion was shifted from a technical one – one must not be the origin of a delay – to an organizational principle: one must cooperate.

A few months later, the punctuality jumped from 80 to 95 percent in all the lines that implemented this approach – without more trains, more time, more people, more systems. The context now rewards cooperation.

If you think about it, these people had been using their intelligence, their adaptability, their skills, their common sense, their energy to work independently from others. Now they are using the same individual intelligence to cooperate, to work as a team. You can see the difference it makes.

Yves Morieux is Senior Partner and Managing Director in the Washington office of The Boston Consulting Group (BCG), and director of the

BCG Institute for Organization. He has been with the company for more than 20 years. Morieux's TED talks have more than 5 million views.

Kevin Helliker, Editor-in-Chief of Brunswick Review, edited this article from a speech Morieux delivered at a 2017 Brunswick gathering.