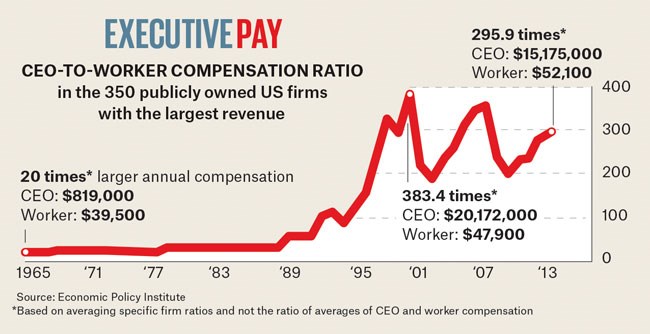

Inequality is rising to dangerous levels. Brunswick’s Jon Miller looks at the ways business may be complicit in this trend and what, if anything, can be done to reverse it

The dramatic and worsening disparity in the distribution of the world’s wealth has become too big for Big Business to ignore. Oxfam recently estimated that the world’s eight richest individuals had the same wealth as 3.6 billion people – the bottom half of the pyramid. Only six years earlier, it had taken 388 individuals to equal half the world’s wealth.

True, some statistics are showing that inequality is actually falling. One key measure of the global economy is inequality between countries. This has, indeed, been falling steadily for the past 30 years as international trade benefits the economies of poor and developing countries. That’s the good news.

Another interpretation suggests that global income inequality has been on a long-term downward trajectory for a century or more. But this amounts to a statistical sleight of hand: as the world population grows, the crowd around the lowest end of the economic ladder is growing, increasing an “equality” that in this case means “equally low incomes.” Meanwhile, the incomes of the few at the top of the ladder soar ever higher.

What is clear is that a vast amount of the world’s wealth is now controlled by a small minority, while billions watch their economic prospects deteriorate – a gap that, as it continues to widen, threatens to destabilize societies and governments.

Business leaders aren’t blind to the problem. Many we speak with are struggling to answer two important questions: How is business complicit in this trend? What, if anything, can be done to reverse it?