Composer George Crumb's scores suggest the mysteries within music, says Brunswick's Carlton Wilkinson

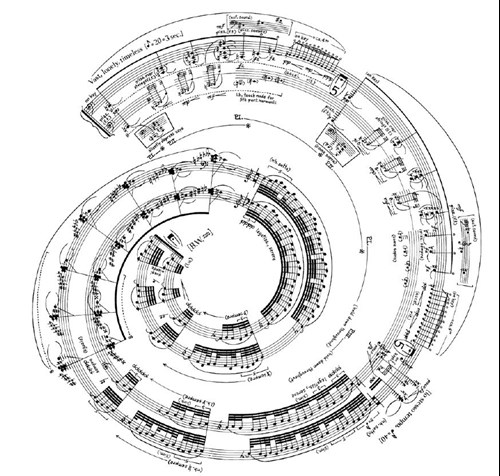

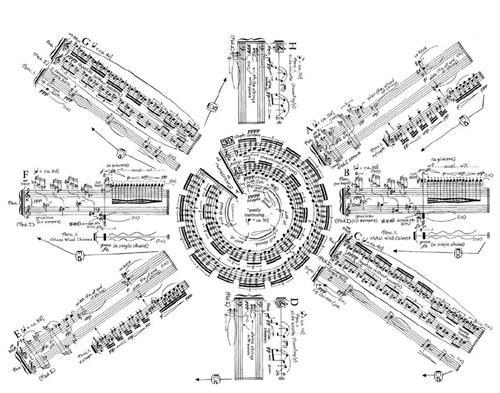

The spell cast by George Crumb’s music often takes hold long before the actual sound. It happens in the pages of his scores themselves. Each is meticulously hand-drawn by the composer, and sometimes he twists traditional notation into a dance of symbols and shapes that help the performer interpret the piece. Like ancient runes or hieroglyphs, these expand the medium of music notation, animating the page and adding layers of meaning.

“I don’t have any artistic skills outside of musical calligraphy,” says the 86-year-old Pulitzer Prize-winning composer in a phone conversation from his home in Media, Pennsylvania. “I just think the music should look the way it sounds.”

Western musical notation dates back more than 1,000 years and is the basis of the classical tradition. It emerged as an aide-mémoire for singers in European monasteries and, over the centuries, has been constantly reinvented. Pitch, loudness, rhythm and articulation symbols are relatively simple, yet communicate complex musical ideas. Crumb’s graphic scores add an emblematic dimension.

Professor Emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania, Crumb says that while most composers now use computers to notate music, “I prefer to do it the slow, old-fashioned way. You have to be like a monk in a cell. You forget time exists.”

Similarly, the sound of Crumb’s music seems to exist outside of time, drawing in passages from historic scores. He finds inspiration in subjects that allude to memory and to experiences of time on vast scales. “People have said that they hear something in my music that is prehistoric,” he says, “evocative of nature and of old-world things that don’t exist any more.”

Crumb is known as much for his experimental sounds as his graphic scores. Footnotes explain the sometimes dizzying array of effects, such as singing into a cardboard tube, walking slowly offstage while performing, or playing glasses tuned with water. These create a sense of ritual and theater.

His audience includes many admirers in and out of classical music circles. The late David Bowie wrote in 2003 that Crumb’s string quartet “Black Angels,” written in response to the Vietnam War, “scared the bejabbers out of me” when he first heard it in the mid-’70s. “It’s still hard for me to hear this piece without a sense of foreboding,” Bowie said. “Truly, at times, it sounds like the devil’s own work.”

Crumb’s scores, drawn on oversized sheets, can take weeks to complete. The resulting work speaks volumes. “Spiral Galaxy” remains one of his favorites. “I’m most proud of that piece, of all my graphic notation. It was so much work.”

There is more to come. He is working on a “large-scale piano piece,” and while he won’t share the details, it is bound to push beyond the limits of both sound and page.

GEORGE CRUMB

Born in 1929, George Crumb is a Grammy and Pulitzer Prize-winning composer. A native of West Virginia, he retired from the University of Pennsylvania in 1997 after more than 30 years of teaching.

Crumb’s scores are not just instructions to the performer. He says, “the music should look the way it sounds.” The musical elements fragment, alternate and repeat in the swirl of “Spiral Galaxy,” (above), from his book of piano solos, “Makrokosmos I” (1972)

In an instrumental interlude from “The River of Life: American Songbook I” (2003, above), percussionists play the center circle music as a loop, while other instruments play each “ray,” separated by pauses

Carlton Wilkinson is Deputy Editor of the Brunswick Review, based in New York.

Image credits:

1. Copyright © 1974 by C.F. Peters Corporation. Used by permission.

2. Copyright © 2003 by C.F. Peters Corporation. Used by permission.