Missed opportunities opened the door to more damage.

Some crises come out of the blue – sudden, unexpected, transforming the horizon and leaving everyone struggling with a new reality, such as when an explosion or earthquake tragically interrupts lives and business routines.

But most crises are not like that. More likely, trouble has bubbled below the surface for some time. Through a mix of inertia, a hope it will go away and the distraction of other priorities, opportunities are lost to deal with problems before they become a crisis.

So it was in 2009, with the scandal over expenses claims by British Members of Parliament. For over a year, parliamentary authorities had resisted efforts by campaigners to force full disclosure of the claims. If the parties had anticipated the inevitable publication, and worked together on how to rebuild public trust afterward, they might well have avoided some of the damage that they eventually suffered.

From my position at 10 Downing Street, I had a front row seat on the crisis’ handling and mishandling. I came away with three broad lessons.

A sounding board is crucial. As the crisis broke, it quickly became clear that the politicians involved found it hard to think objectively about the storm engulfing them. The MPs, including senior Cabinet ministers, felt as though they were being hounded unfairly. After all, they had only been following the rules, hadn’t they? Most had their individual arrangements confirmed through the Commons Fees Office. MPs’ salaries had been flat in recent years and increases in expenses had been seen as an unofficial alternative.

The sense of injustice was real and sincerely felt. Perhaps it was even justified. It was also irrelevant. Everyone else, including those of us advising the politicians, thought that something had gone badly wrong. Before we could bring about change, the elected politicians on both sides of the aisle had to change their mindset.

You need to show you “get it.” I remember the moment that the depth of public anger first hit me. A senior Minister was preparing to appear on the BBC’s flagship “Question Time” program. She was a real pro, confident and reliable in media interviews. Yet her attempt to give a rational explanation for what had happened quickly turned into a car crash. The audience jeered and booed and shouted out their objections. For the first week of the scandal, it was impossible to communicate any message publicly until we had shown that we “got” the level of public anger. This could not simply be a bit of throat clearing at the start of the interview before moving into a justification. The public needed to hear contrition. Then they needed to hear it again. Only once we had successfully conveyed that with sincerity were we given any right to be heard on proposed solutions.

The crisis is not the only thing happening. The country was in the midst of a recession and the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis. Labour was deeply unpopular. There was dissatisfaction over Mr. Brown’s leadership. The Cabinet was divided on economic policy. The wider party was split over issues such as the proposals to bring private capital into the state-owned Royal Mail.

This context had two specific impacts. First, given these other demands, the expenses scandal could never take up more than a small proportion of the Prime Minister’s time.

Second, the government’s options were politically constrained. Any appropriate course of action also needed sufficient parliamentary and cross-party support to be sustainable.

This applies to any crisis: Proposed solutions should not simply be an unrealistic ideal. They can be ambitious – but they must also be practical and deliverable.

Stuart Hudson is a Brunswick Partner in London and a former Special Adviser to the UK Prime Minister.

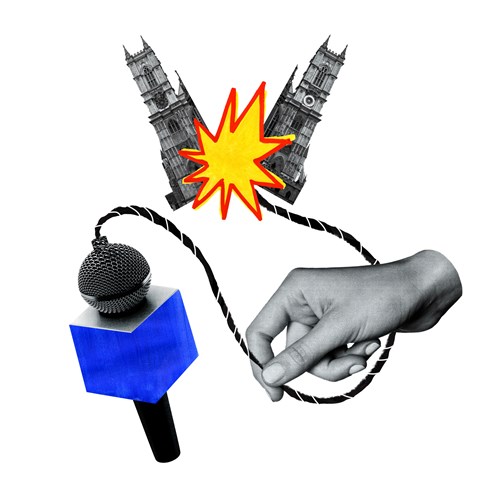

Illustration: Franziska Barczyk