That’s surprising coming from someone known for pushing back in the C-suite and the boardroom. After all, you all but invented the idea that disruption should be rewarded.

Most of us are trained to work in teams – don’t make waves, don’t disagree with people, try to find consensus, et cetera. That doesn’t work. If everybody just sits around being nice to each other, absolutely nothing gets accomplished. If what you’re doing is no longer competitive, somebody has to say, “We should change this.”

What I heard my whole career was, “That’s a very good thought, Bob. But at your level, we expect you to just follow orders.” I would say, “I realize that, Sir. And I’ll do whatever you tell me, but I felt it was important to point out that we are doing this wrong.” That attitude gets you in trouble.

One boss or the other would say, “Bob, we’ve heard you, we respect your opinion, we’re not ready to change.” I would say, “Thank you very much for listening, Sir.” Then I’d back off. You have to know when to stop.

What was the difference between the GM you left in 1971 and the GM you rejoined in 2001?

In the 1960s, GM had the best cars, the best styling, the best engines, the best everything. You know, the big Chevrolet Impalas, Oldsmobile Cutlass, various Pontiacs, the big Buick Riviera. Back then, General Motors had to be careful not to get over 60 percent market share in the United States because they were starting to draw the attention of the antitrust people. GM back then was a very product-focused company.

But over time, especially in the ’80s and ’90s, GM became increasingly focused on cost reduction. It forgot that you cannot save your way into prosperity.

I was hired because Rick Wagoner [GM CEO from 2000 to 2009] asked me, “What do you think is wrong with GM?” After my 30-year absence, there was nobody left at GM who had served in a senior capacity for the company in the 1960s. I gave Rick an earful. A few weeks later he hired me as vice chairman and my whole job was to get GM off of this robotic, bureaucratic, formulaic approach to product and get them back to enthusiastically designing and building the best product. Basically, to get General Motors back into the car business.

In the years that followed, any number of launches or redesigns – Chevy Volt, Buick Enclave, the Camaro, GMC pickups – won acclaim. Even the Malibu, which had become a ho-hum rental-car sedan, emerged from a redesign as the North American Car of the Year. How’d you do that?

It was a process of reversing the prior policy of how little do we have to put in the car in order to have a viable entry in the marketplace. That philosophy was minimal, minimal, minimal.

I pushed the approach of let’s give people something fantastic that will wow them. Drivers look at it and say, “Holy smoke, I get all this for $22,000?” Of course, all the finance people were wringing their hands, saying, “Oh, Bob, what you’re doing is terrible. You’re putting more money in the cars.”

I said, “What happens when our cars reach the market? We have to put $4,000 rebates on them to sell them. What does that do to the margins?” I said, “Let me put 500 bucks of visible, tangible customer value into each car and bring them up to a competitive level or, if possible, a bit beyond competitive. And then we will reduce the average incentive from $4,000 to $2,000. I’m saving you $2,000 per car, and it’s taking me $500 to get that $2,000.”

Did the financial crisis slow that transformation?

A lot of things that we wanted to do had to be deferred, in some cases up to two years. But it turned out that our competitors had the same problem. Everybody cut back their product plans.

In a 2017 Automotive News column [see excerpt] you predicted humans would be all but absent behind the wheel in 20 years. At the same time, you have made waves for slamming the short-term potential of electric cars, Tesla in particular.

Long term the potential for electric cars is good because the cost of batteries will come down, the cost of all the electrical systems will come down.

But until then, electric vehicles are so-called compliance cars, made to comply with zero emissions regulations as postulated by California and 13 or 14 other states. Every maker is doing electric cars because they have to. But Mercedes, BMW, Audi, General Motors, et cetera, can afford to sell electric cars at a loss, because of the profits they make on their big gasoline-powered vehicles. Tesla has no gasoline cars on which to recoup that money.

Kevin Helliker, a Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist, is Editor in Chief of the Brunswick Review. He is based in Brunswick’s New York office.

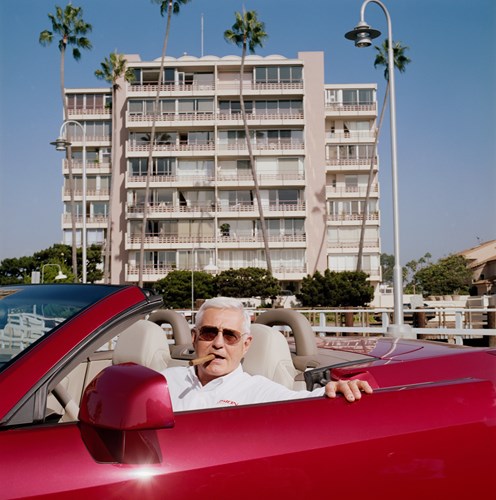

Photogtaph: Bryce Duffy/Corbis via Getty Images